You are in:

Centenary Amazon

How to browse

Click on the icons to move around the room or to access points of interest. Alternatively, use the arrow keys to turn, go forward, and go backward.

Click and drag the image to explore the scene in 360°.

Alternatively, use the arrow keys to turn left and right.

Use the scroll wheel to zoom in or out.

Alternatively, use the plus and minus keys.

Virtual Tour / Texts, maps and data on the topic

Texts, maps and data on the topic

INTRODUCTION

“The best place in the world is here, and now.” Gilberto Gil’s song helps to define a little of the life of traditional riverside and extractive populations in the Amazon: the present is the best time to live, produce and trading food for sustenance. The fisher, farmer, rubber tappers, and the babassu kernel breakers understand Amazonian time very well, different from the chronological time we are accustomed to. The floods and droughts define family plans and interaction among communities.

It is difficult to think on a long-term basis when one knows (or does not know) when the waters will flood fields and pastures. Understanding nature’s cycle in the Amazon is essential for survival.

TRADITIONAL COMMUNITIES

The two seasons

The Amazonian residents are used to a different weather cycle than normal seasons. Fall, winter, spring, and summer are not like other regions in Brazil. The year is divided into two great meteorological moments – the flooding and dry seasons. The terms winter and summer refer popularly to heavier and lighter rainy periods.

That does not mean that the changes in flooding and decreased rainy periods will coincide with normal seasons, as the water level of the river begins to decrease at the end of the rainy season and the dry and rainy seasons start earlier in the upper parts of the river.

These changes are considered essential in the Amazon, since people need to pay attention to fish migration, shifting positions of animals, soil hardness, the growth and death of plants, winds, and rains. Adaptability has been affected by climate change, for example, interfering in natural cycles and making the life of the riverside people more difficult.

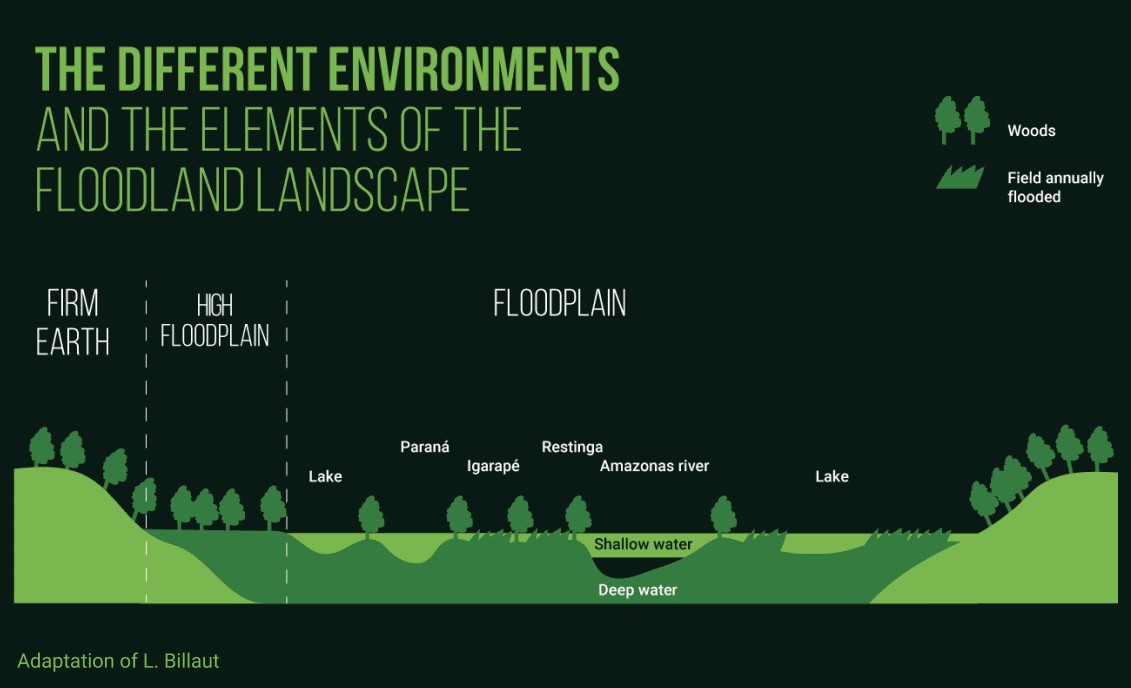

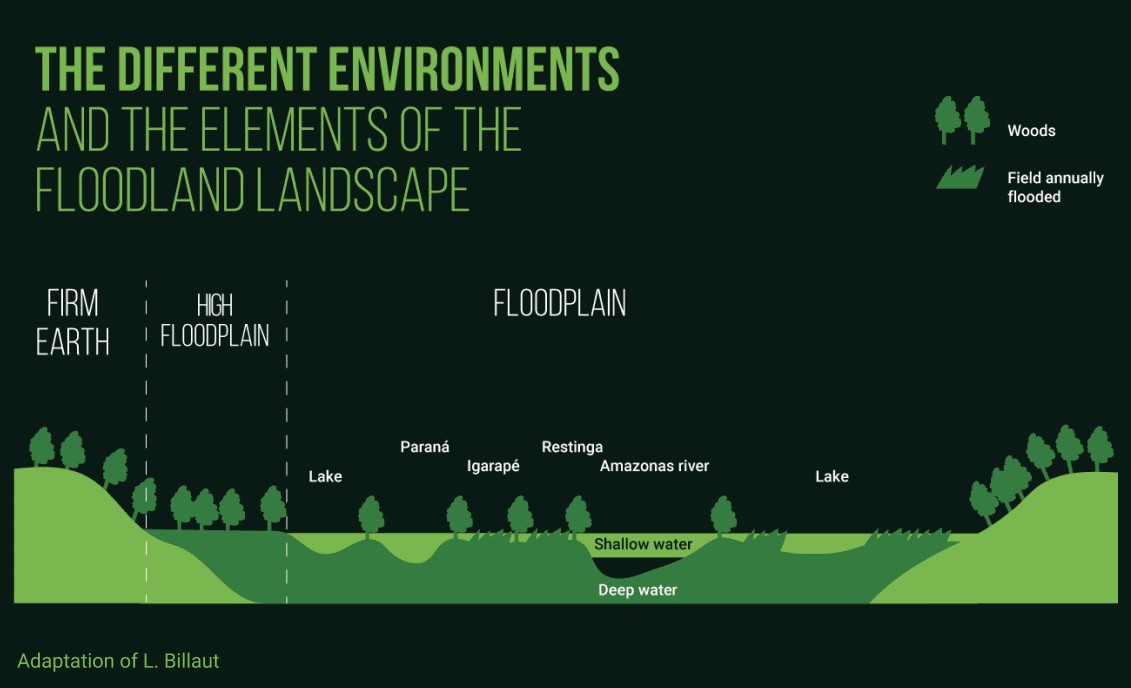

The floodplain

The people living in the floodplain area of the rivers need to deal with seasonal variations. Flooded rivers make entire communities set up housing above the high-flooded-water levels. The buildings on stilts are supported by wooden poles internally adapted to the river water level using “marombas” (balancing poles), and the floors of wooden houses adjust according to the water level. The exact height, extent, and speed of the flooding is not known in advance confirming if the river will rise or fall, leading residents to always deal with the unforeseen.

Communities also face the phenomenon of landslides, erosion from riverbanks during periods of drought and they have become even worse due to deforestation. These risks do not prevent communities from adapting to the new reality, however they affect the social, economic, and environmental aspects of the region.

The residents of the Amazon floodplain live at a particular time pace and face a several of challenges due to unpredictability, but they know how to take advantage of adversity and create income opportunities. The remains on land from the previous year activities disappear after each flood, but afterwards when the water level drops the soil becomes richer in nutrients for crops. Fishing becomes more prevalent during the flood period.

The riverside dwellers depend on working the land for subsistence farming, livestock ranches and vegetation extraction as well as access to water-based work for subsistence-based fishing or trading.

Dryland communities

Extractivists in dry land regions, – such as rubber tappers, as proven by Chico Mendes’ struggle in the 1980s – they are one of the largest groups of traditional populations surviving from natural resources – in this case, latex (or natural rubber) extracted from rubber plantations.

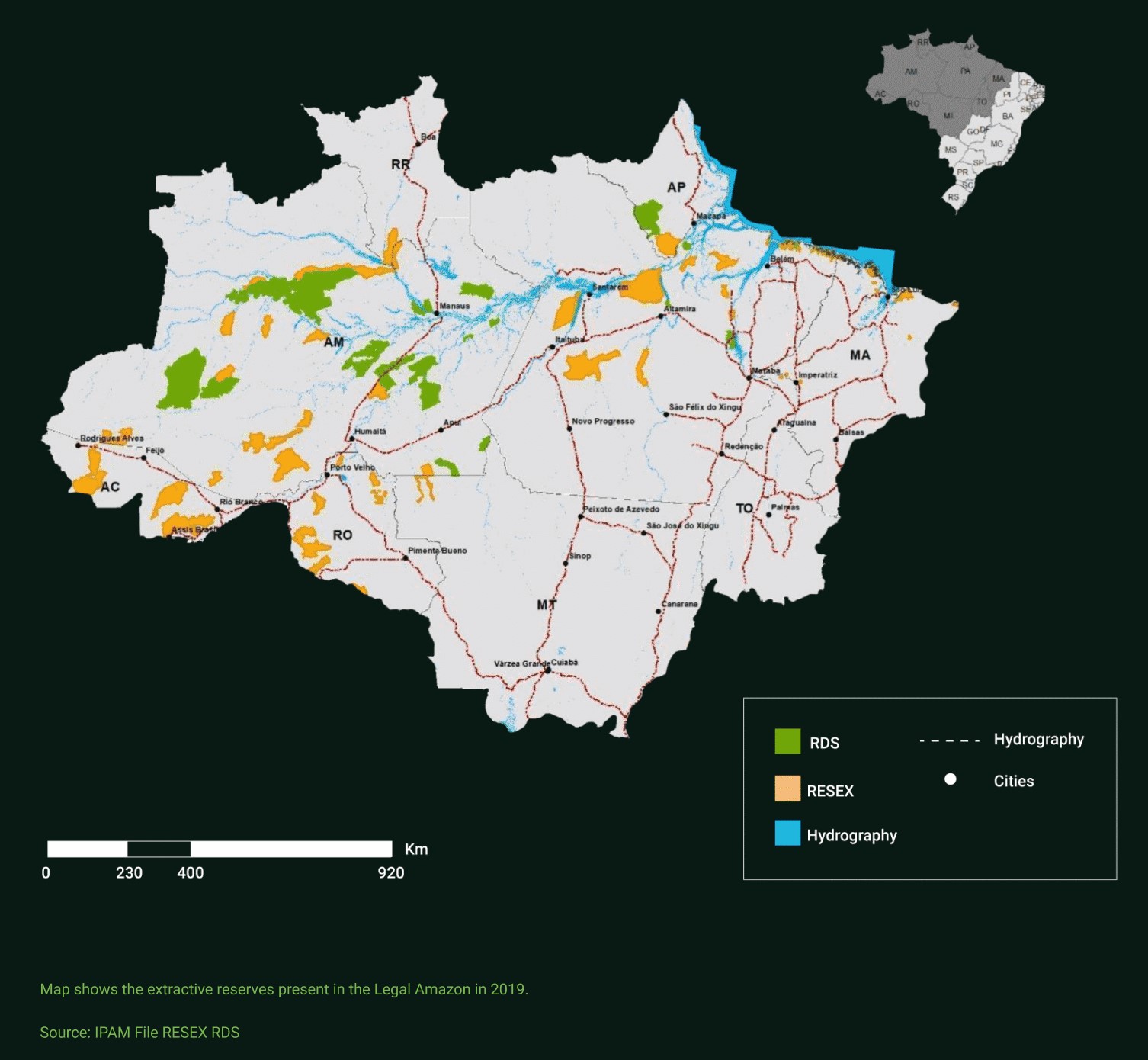

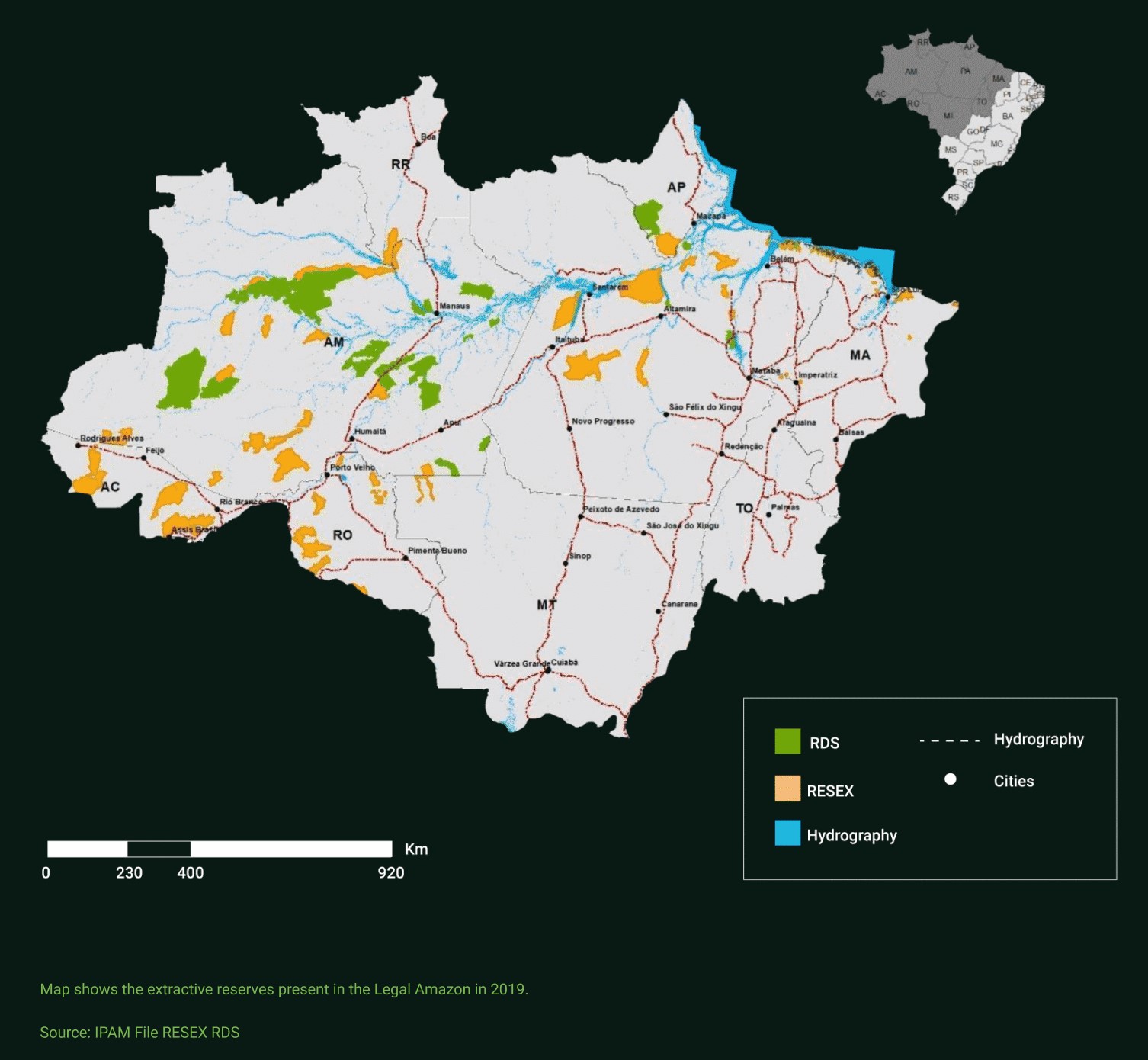

Data from the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio) show that by 2019, the Amazon region was home to 104 extractive reserves and sustainable development reserves, distributed in nine states, covering about 5.1% of the biome territory (258,928 km2). According to the National Council of Extractive Populations, approximately 1.5 million people benefit from these reserves and the work from the extractivism there.

There are also “piaçabeiros” (people who extract piassava), who make a living on extracting this fiber from the piassava palm tree (used in manufacturing brooms), and the “peconheiros” (açai berry collectors), who climb – sometimes unprotected – to the top of the palm trees to harvest the fruit of the açai palm tree.

Most of the 400,000 babassu coconut crackers in Brazil are in the Amazonian states of Pará, Tocantins and Maranhão, according to the Interstate Movement of the Babassu Coconut Crackers. These workers have been collecting coconuts and cracking them in half to mostly to extract their almonds for generations that produces one of nature’s most versatile oils.

Although they live well in the forest – and they extract their livelihood there – traditional communities face various conflicts in their territories, such as the construction of infrastructure projects, thermoelectric plants, hydroelectric plants or even roads, in addition to advancing agribusiness and land grabbers. According to the Conflict Map Involving Environmental Injustice and Health in Brazil, developed by Fiocruz, there are in the nine states of the Legal Amazon at least 96 conflicts going on, that have been registered, since 2006.

There are also traditional populations, such as “quilombolas” (Afro-Brazilian maroon people), a population descended from enslaved people living in untouched areas of the forest and helping to preserve the ecosystem. According to the “Pró-Índio” (Pro-Indian) Foundation, there are in the Amazonian biome, 743 “quilombola” lands, their deeds have partially been granted, or they are in the process of regularization at the National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform, Incra.

THE ECONOMY OF TRADITIONAL POPULATIONS

Biome-based economy

The productive systems of the countryside economy underlie a broad-based rural economy in the Amazon. In the 2017 Agro Census, conducted by IBGE, almost 200,000 production units were recorded in this convergence pattern, occupying an area of 8 million hectares, where 430,000 workers are employed throughout the Northern Region of Brazil. The value of rural production was R$ 4.8 billion in 2017 – it was R$ 3.3 billion in 2006: an annual increase of approximately 3.6%.

The institutional environment of the government seems to be unfamiliar with this economy – the rural economy is the region with a lower share of credit and technical assistance policies: only 6% of its establishments declared to have access to credit in the agricultural census in 2017. Even though the main options are for the countryside producer, commercial fishing and livestock, meanwhile, are two of the main threats to the social and environmental sustainability of the communities.

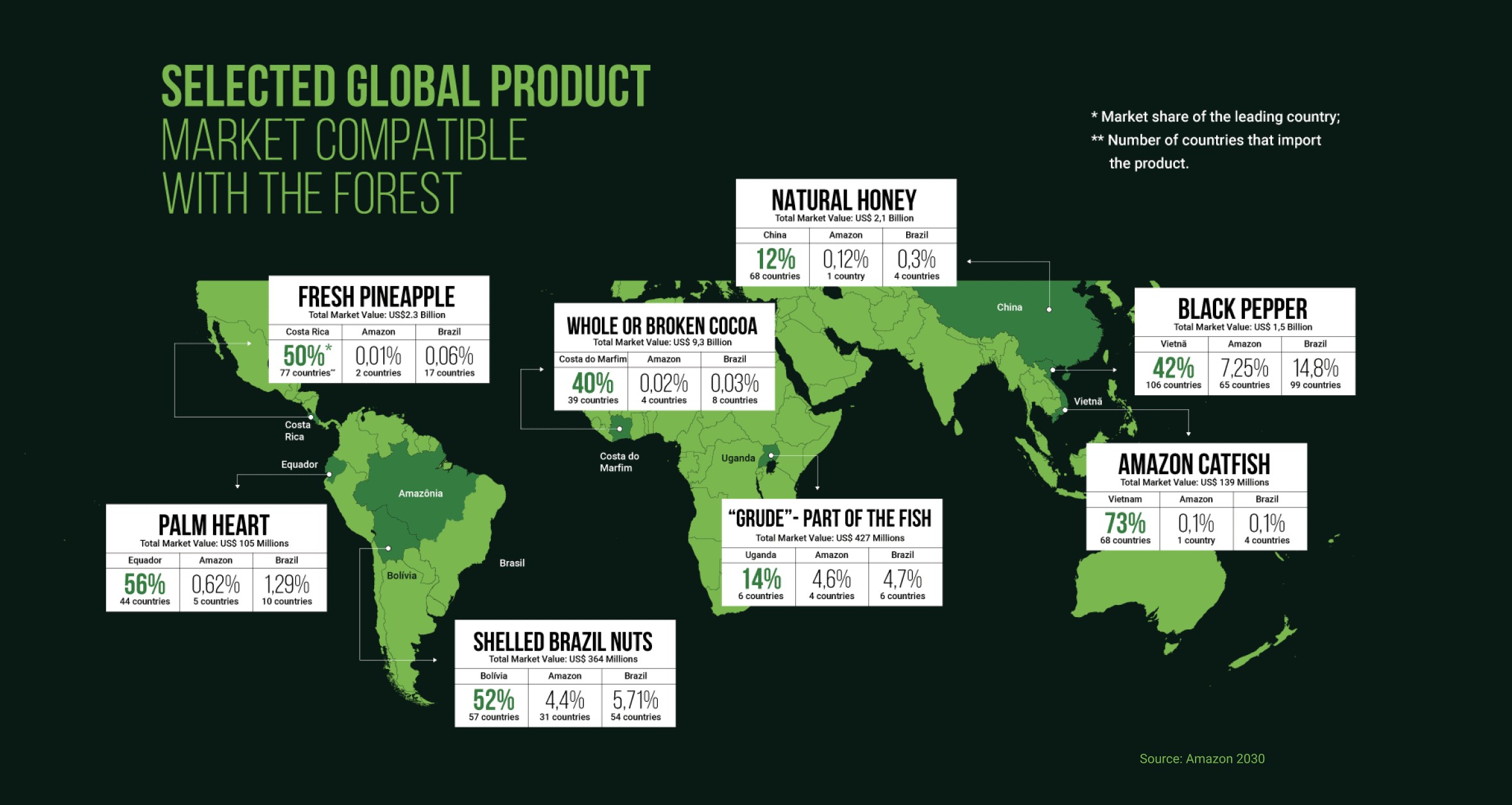

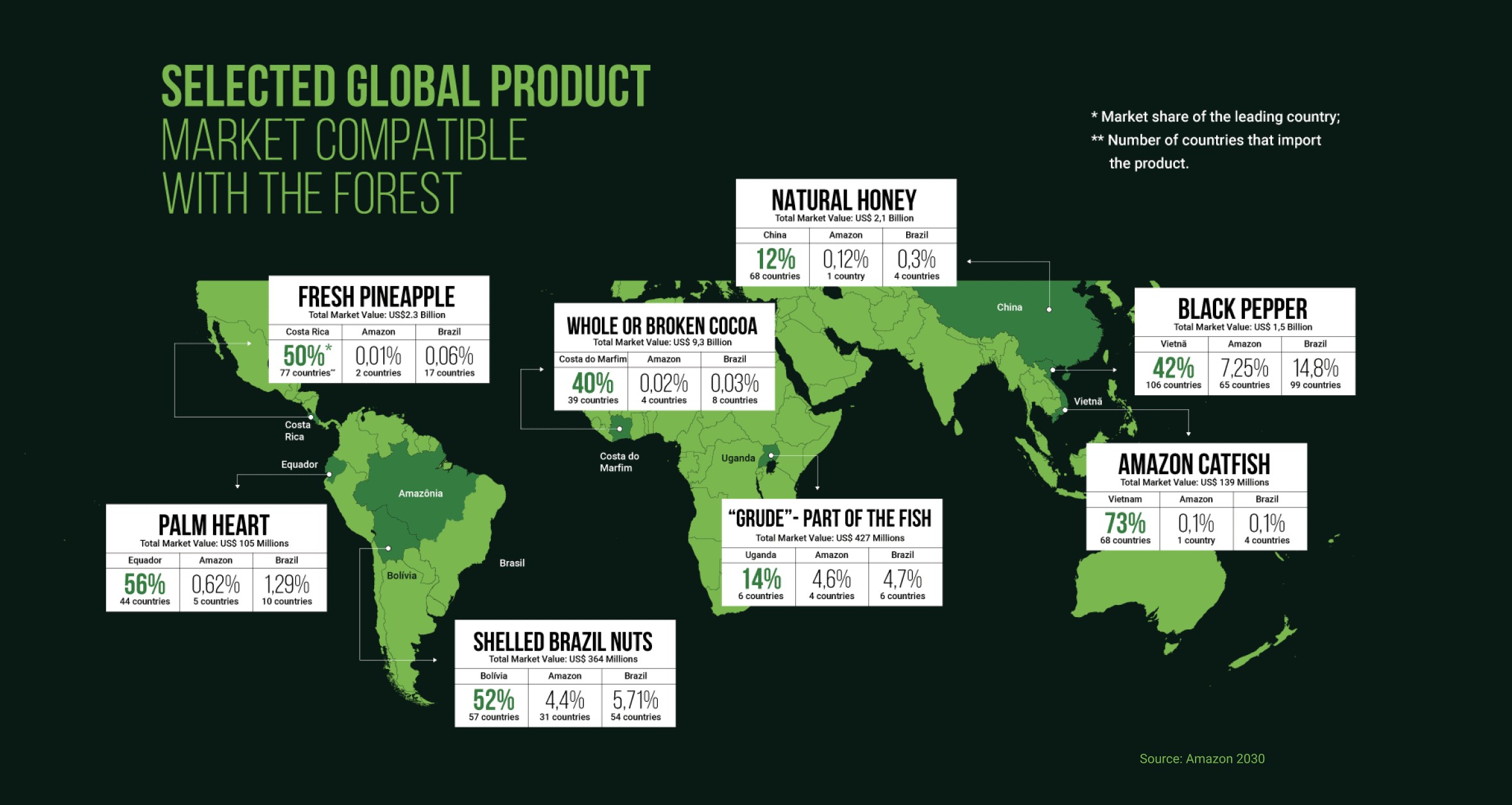

Untapped potential

Natural or lightly processed articles are products compatible with the forest from non-timber forest extraction, agroforestry systems, fishing, tropical fish farming, and tropical horticultural. These products transact billions of dollars worldwide, but currently, their main exporters are, in most cases, smaller economies than Brazil. The Vietnam case, the main exporter of black pepper.

The low net CO2 emission is a common feature of the biome-based economy. It is estimated that, even though this economy is growing, it reduced the net emission of CO2, which was already the lowest in the entire rural economy of the Amazon in 2006: it went from 0.5 gt to 0.3 gt of CO2 from 2006 to 2017. The carbon density (the volume of CO2 released into the atmosphere for every R$ 1.00 billed) that was also very low, went from 0.17 tons of CO2 in 2006 to 0.08 tons of CO2 in 2017.

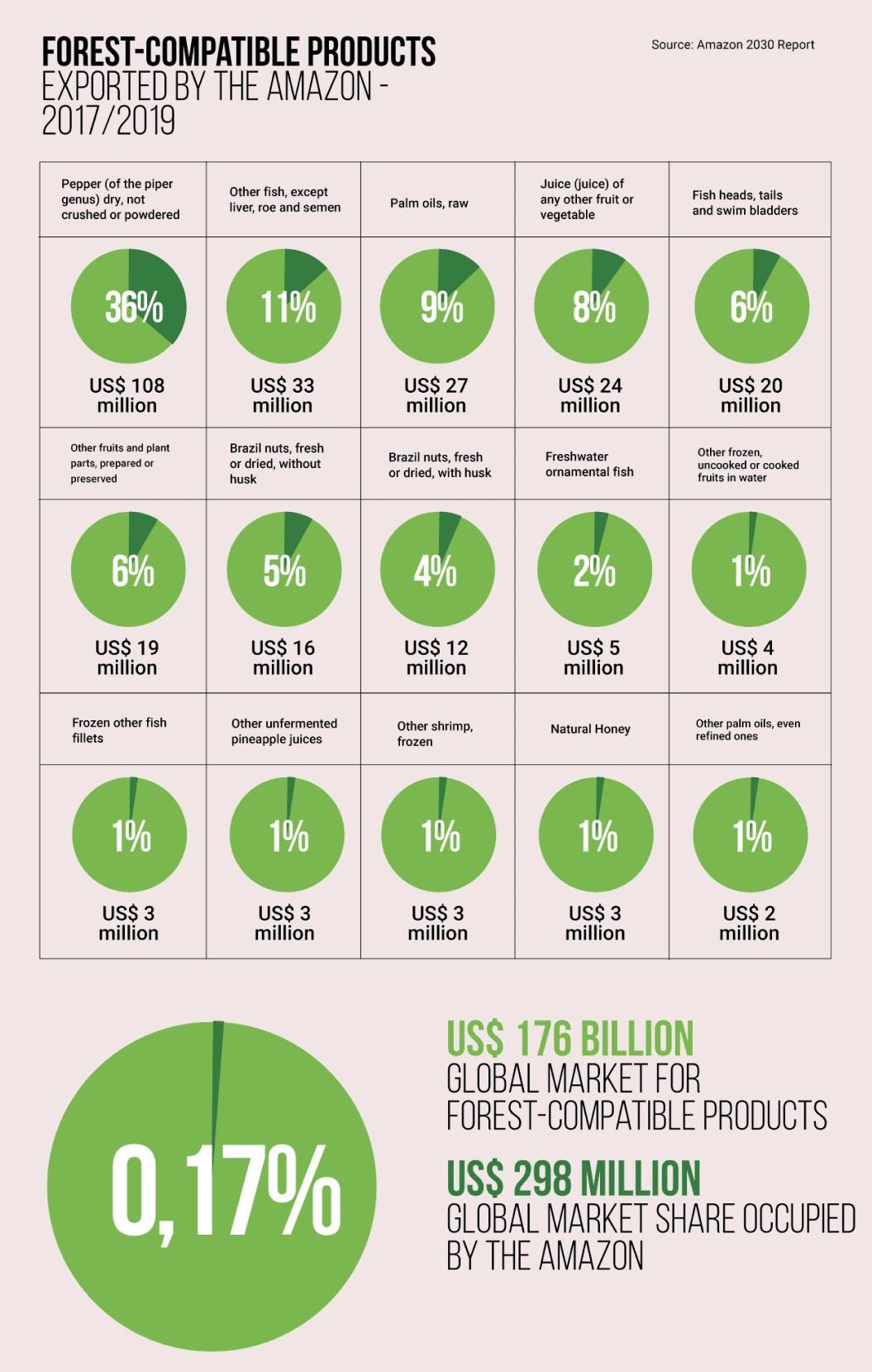

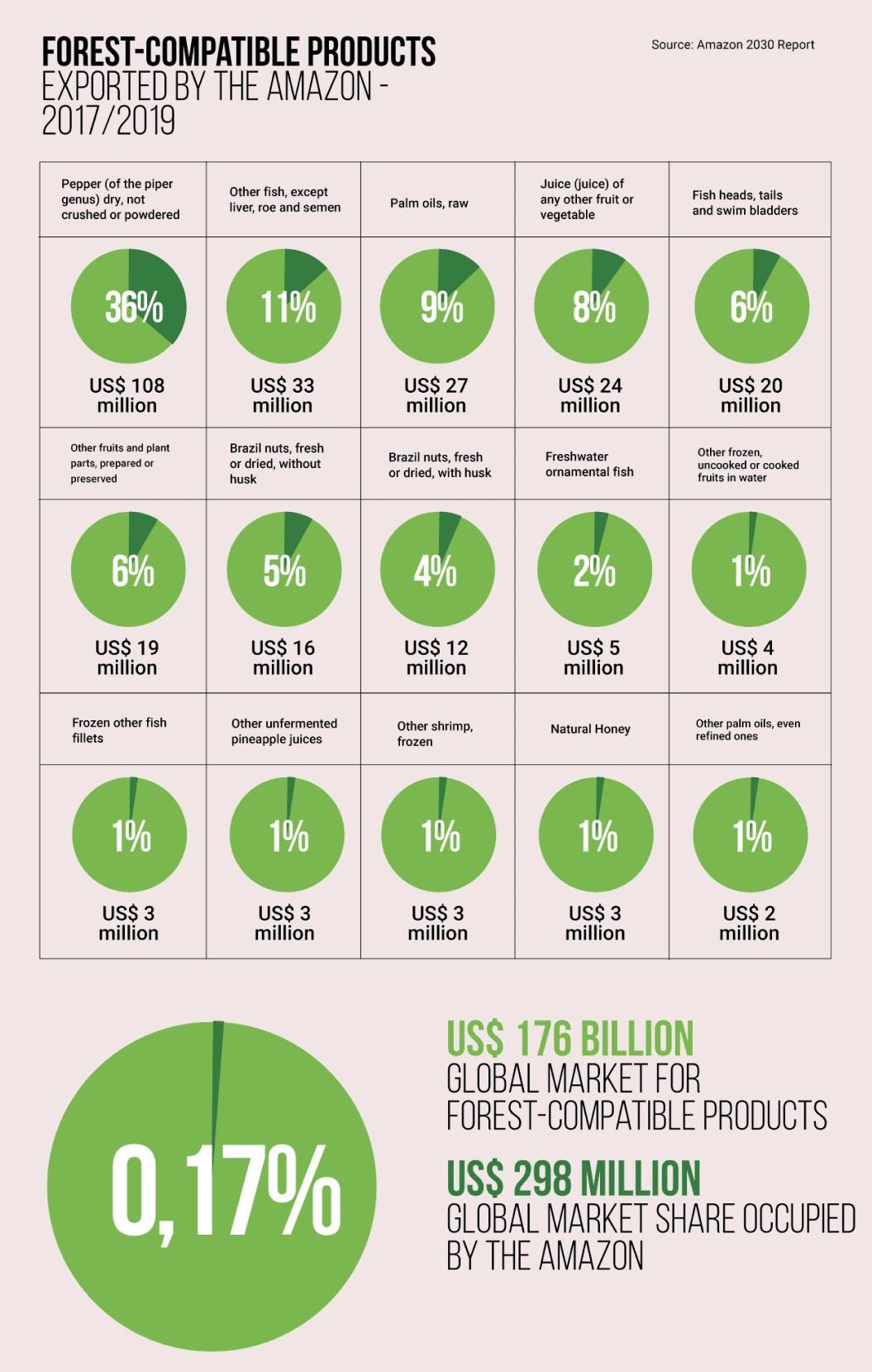

Current resource exportation

According to a study carried out by the Amazon 2030 project, linked to environmental institutions and the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio), the main products exported from the Amazon during the period 2017-19 came from mechanized agriculture (soybean, corn, and cotton), mineral extraction (iron, aluminum, copper, and gold), livestock and paper, and cellulose. But the researchers claim that the attention focused on these products hides a longer list of product types that are already traded abroad and do not impact the forest in the same way.

From January 2017 to December 2019, companies located in the Amazon exported 955 different products, 64 of which resulted from non-timber forest extraction, agroforestry systems, fishing, tropical fish farming, and tropical horticultural. These articles have already been exported by the states of the Brazilian Legal Amazon for transaction in a billion-dollar global market, dominated by countries such as the Ivory Coast (in the case of cocoa) and Bolivia (in the case of shelled Brazil nuts). The Amazon can expand its participation in this global market to generate income and boost the region’s economy.

Products such as palm oil are well known due to their versatility and widespread use in the food, cosmetics, food, and biodiesel industries. But others such as fish heads, tails and bladders are more unusual or exotic.

In most of Brazil (and the world), fish guts are discarded or used to produce fertilizer or animal feed. In the three-year-period 2017-2019, companies based on The Legal Amazon exportation, an average of 620 tons of “grude” (a sticky substance) and invoiced about US$ 19 million per year. These products may seem prosaic, but they transact a lot of money.

The enormous size of these markets reveals the low performance of exports from the Amazon region. Pepper was the highest volume of any exported agroforestry product from the Amazon, but the region accounts for only 7% of this global market. In the case of “other frozen fish”, the share was lower (0.8%). In the case of tropical fruits, such as cocoa, pineapples, guavas, mangoes, and mangosteens, the performance of the Amazon was even lower, from 0.005% to 0.015% of the global market.

How can traditional production be increased sustainably?

The knowledge that enables the efficient and sustainable exploitation of biome resources by traditional populations is largely constituted by cultural repertoires inherited from indigenous peoples or families who colonized the Northern region in past centuries. However, a science, technology, and innovation (ST&I) strategy would be needed to aim at new competencies for a future to protect the capabilities of the Amazon biome and offer dignified lives to those who interact with the forest, its productive and reproductive processes.

To do this, we will need:

- Develop basic and applied knowledge that focus on production systems and their long-lasting reproductive ecology;

- Adapt and adjust knowledge to different territories to the needs of this economy with sustainability;

- Think about technological solutions that facilitate logistics and avoid losses in production;

- Design equipment technologically and the means of production to meet the needs of biome-based production;

- Qualify labor;

- Develop production and logistics solutions considering the needs of short supply chains focused on local markets that are very important to the biome-based economy;

- Develop production and logistics solutions considering the needs of the chains focused on the national market that are very important to such products as açai and cocoa;

- Adapt to the requirements of the international market, which establishes phytosanitary standards;

- Adopt good social and environmental practices, independent verification systems, and certifications.

How can I contribute?

As a consumer, you can also perform day-to-day actions to appreciate bioeconomy products and the work of traditional amazonian populations:

- Get to know the Amazon cuisine and the local food consumption mode. For example, learn how the açai berry is consumed in the Amazon, as a savory food served with the main meals of the day;

- Prioritize the consumption of certified products that are part of a sustainable production chain, especially the meat, fish and fruit chain;

- Monitor the brands you consume, searching, for example, for credible reports on the production mode of companies;

- Value small regional producers;

- Read authors of the classical literature of the Amazon, portraying the riverside life and the sociobiodiverse economy. For example, Dalcídio Jurandir, Inglês de Sousa, Benedicto Monteiro, among others;

- Vote for political representatives who are active in initiatives related to forest conservation in their management plans.