You are in:

Accelerated Amazon

How to browse

Click on the icons to move around the room or to access points of interest. Alternatively, use the arrow keys to turn, go forward, and go backward.

Click and drag the image to explore the scene in 360°.

Alternatively, use the arrow keys to turn left and right.

Use the scroll wheel to zoom in or out.

Alternatively, use the plus and minus keys.

Virtual Tour / Texts, maps and data on the topic

Texts, maps and data on the topic

INTRODUCTION

According to a geopolitical view of the government, the Amazon was occupied with filling what was called a “demographic vacuum”, in the 1960s. Significant investments were made to set up agriculture, mining, infrastructure projects, economic development models based on developmentalism. This land occupation view is based on economic growth and not on regional development and it continues even nowadays. The countless infrastructure investment plans have imposed an immeasurable socio-environmental cost on the region.

LAND OCCUPATION POLICIES

The occupation of the Brazilian Amazon was limited to the coastal region and strips of riverside lands along the main navigable rivers for a long time, as during the cycles of exploitation of so-called “backcountry drugs” during the colonial period. In the 19th century, rubber harvesting and other production systems were based on extractivism exerted little impact on forest cover.

Since the 1970s, the Brazilian federal government has structured a land occupation policy based on agricultural colonization and infrastructure investments, especially preparing new roadways. Livestock farming was a privileged activity in this period, providing strong financial incentives for those who ventured into the region. These new fronts for expanding the agricultural frontier have transformed land uses in the Amazon.

In 1960, 5.4 million inhabitants were living in the Brazilian Amazon. According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics estimate, in 2021, 29,650,663 people are living in the Brazilian Amazon – more than five times the population of six decades ago. More than 80% currently lives in cities. A whole set of infrastructure work projects is currently being triggered in this region, following a pattern of non-sustainable development, similar to what occurred in the 1970s.

Affected quality of life

Informal jobs, poor sewage treatment and access to drinking water, and low family income surrounded by a high concentration of wealth in more populated urban centers are some of the critical problems felt by residents of the Amazonian states.

Information from the Atlas of Human Development (MHDI) 2020, organized by the United Nations (UN), shows that life expectancy in all states of Legal Amazon is below the 75.99 National average; and the infant mortality rate in all states is higher than the 12.38 National average; The per capita income in the Amazon region have a lower income than the Brazilian average of 834.31.

The labor market in the Amazon is marked by a high degree of informality and low wages compared to the rest of the country. In Legal Amazon, 6 out of 10 workers are informally employed. Additionally, the average income in the region is 29% lower than in the rest of Brazil.

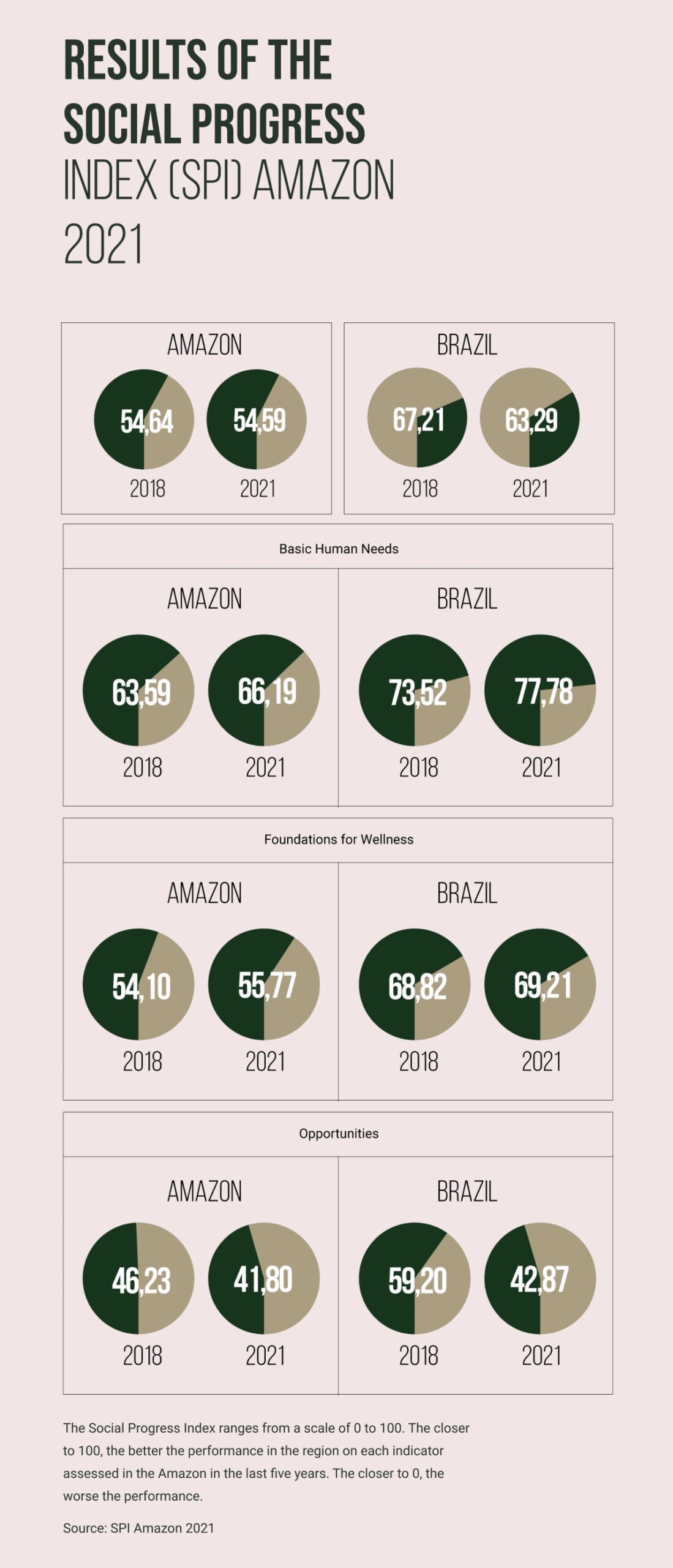

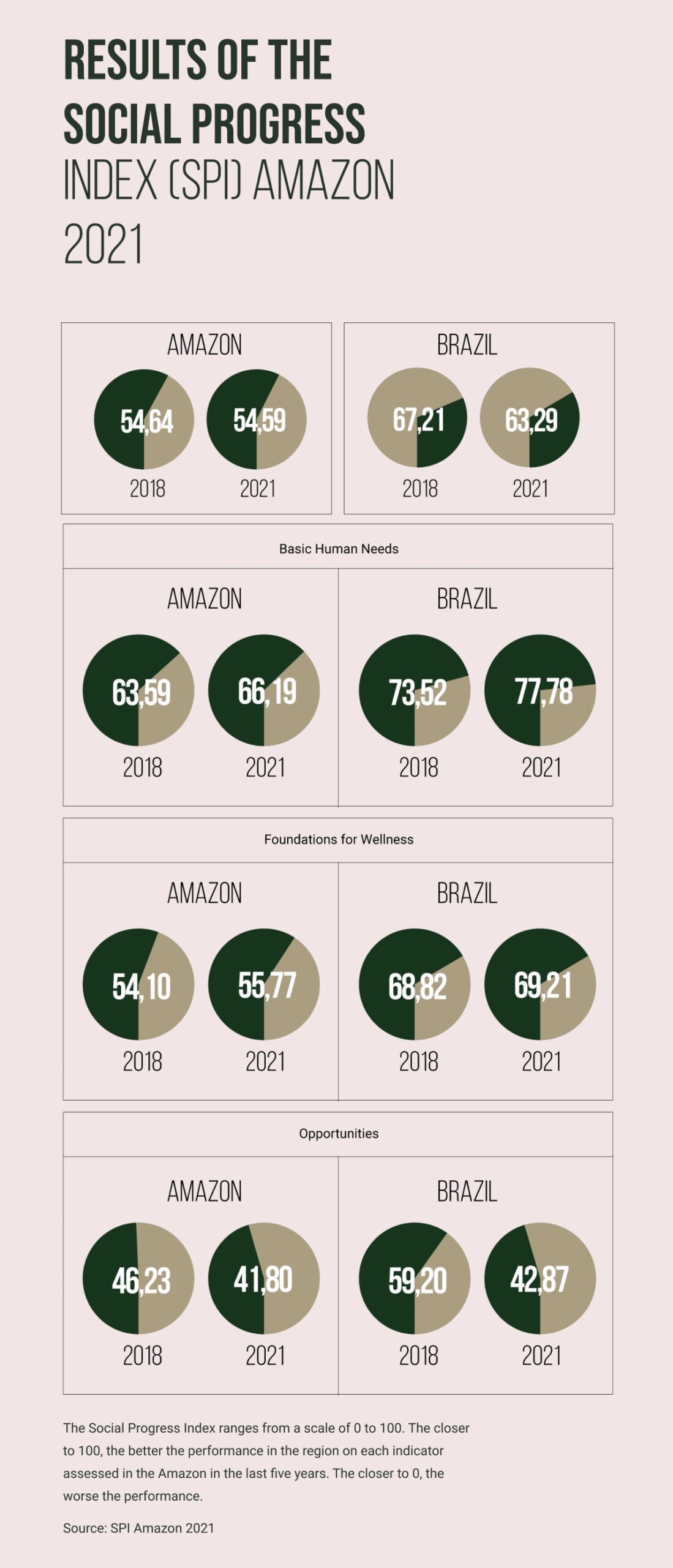

A critical study that measures social performance in the region is the Social Progress Index (SPI), conceived by Imazon. The Amazonian SPI displays a detailed X-ray of the social and environmental status of all 772 municipalities in the Amazon, presenting data related to basic human needs, fundamental to well-being, and opportunities for educational development and income generation.

Sewage treatment and access to drinking water in cities

According to statistics from the Brazil Sanitation Panel, organized in 2019 by the Trata Brasil Institute and exchanges information with the Unified Health System, the rates of sewage collection in all Amazonian states is much lower than the national average. In at least four states (Acre, Amapá, Pará, and Rondônia), more than 50% of the population do not have access to good drinking water. Also, according to the survey, the consequence from this lack of water supply provokes a high number of hospitalizations related to water-related diseases (85,143 cases, 31% of the national amount).

Urban and rural violence

According to the Atlas of Violence 2021, organized by the Institute of Applied Economic Research (IPEA), Acre, Amazonas, Roraima, Pará, and Amapá are among the states in the federation with the highest homicide rates per 100,000 inhabitants. Disputes between criminal factions for the leadership of territories and the control of drug trafficking have caused increased crime in the region. In Roraima, the social crisis caused by the mass migration of Venezuelans has put pressure on social conditions in the state due to the economic situation in the neighboring country.

Violence in the countryside due to land disputes and land grabbing is still present in a remarkable way. According to reports of the Pastoral Land Commission, in 2020, 53.6% of land conflicts in Brazil have occurred in the Legal Amazon.

THREATS TO THE FOREST

Forests under pressure

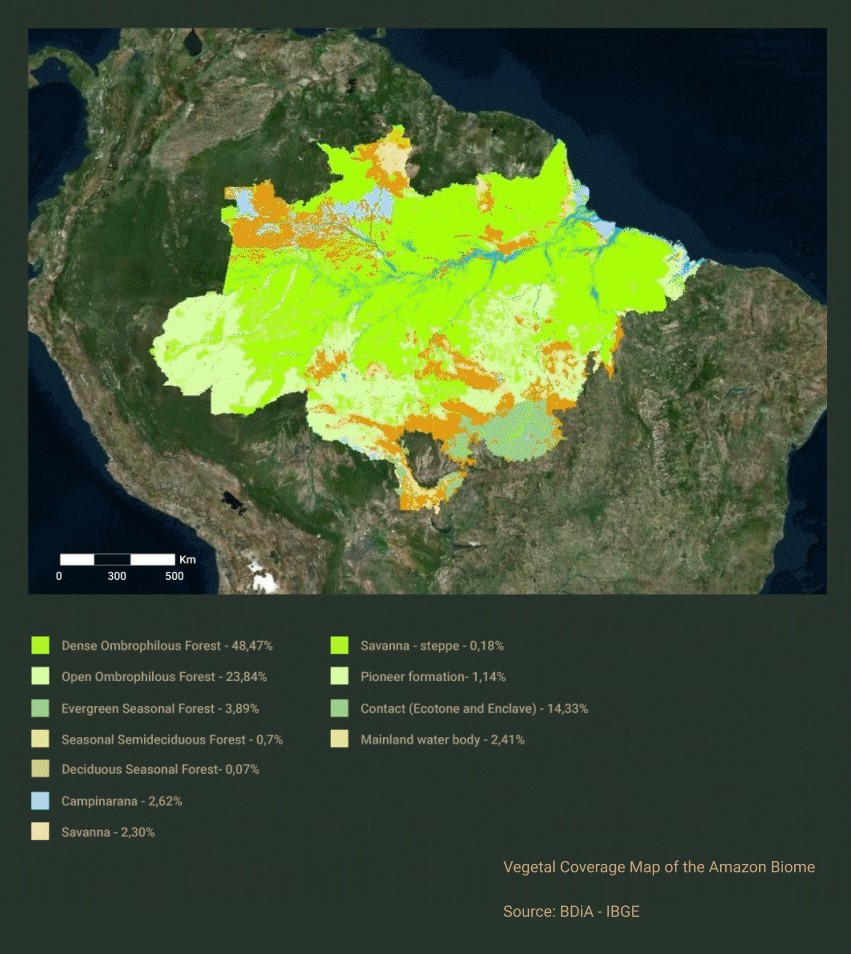

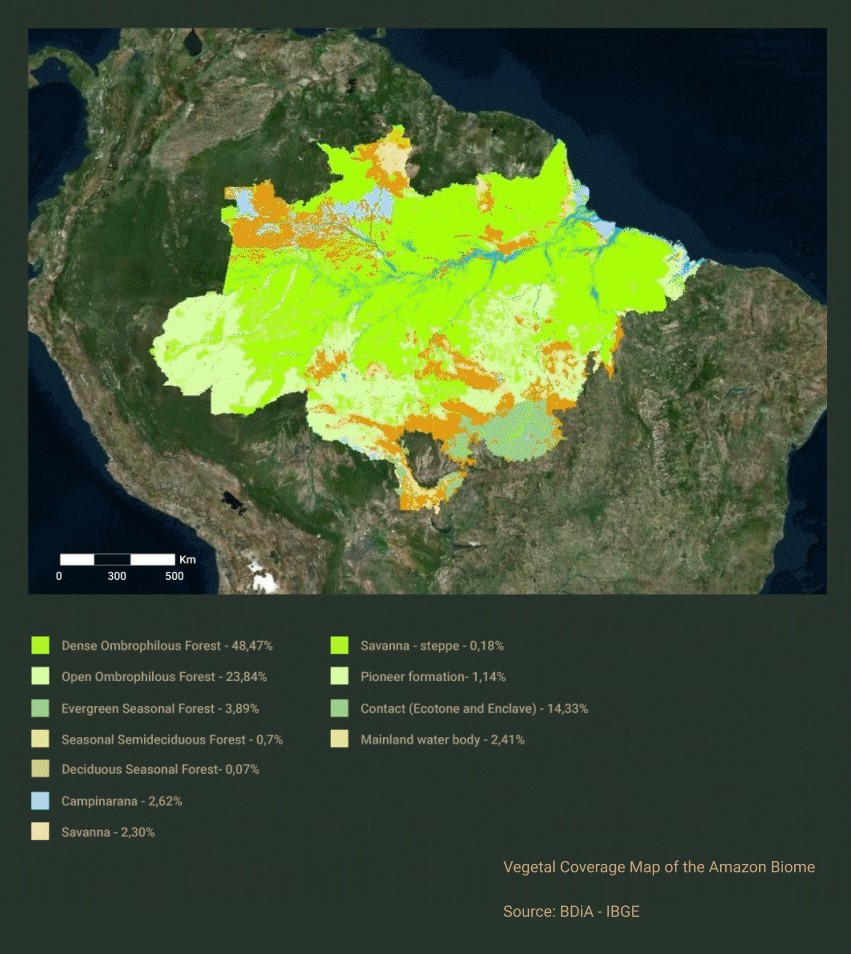

The Amazon is the largest Brazilian biome in extension and occupies almost half of the national territory. IBGE recognizes four major floristic regions in the Amazon: Dense Ombrophilous Forest, Open Ombrophilous Forest (palm forest, bamboo forest, “sororoca” (a broad-leaf type of vegetation) forest, and “cipó” (vine) forest), “Floresta Estacional Sempre-Verde” (Ever-Green Season Forest) and “Campinarana” (white-sand vegetation).

The Dense, Ombrophilous Forest, known as forests or solid-ground forests, is predominant and the richest in terms of biodiversity and can include hundreds of species in a single hectare. These forests are always green with no notable variation in seasons. And the emerging stratum is composed of tree species that reach about 45 meters high. Human beings exert the most significant pressure on these.

Amazonian Deforestation

Deforestation is the extraction of extensive stretches of forest lands through shallow cutting (felling all trees) and burning, carried out mainly to transform the vegetation into pasture for cattle raising or monoculture of some plant with high market value.

The destruction of the Amazon rainforest reached the highest annual rate in 2021, since 2007. The consolidated value of the deforested region by shallow cutting from August 1, 2020, to July 31, 2021, was 13,235 km2, an increase of 21.9% compared to the deforestation rate determined by PRODES in 2020, which was 10.851 km2 in the nine states of Legal Amazon.

However, in recent years, there have been indications that the profile of illegal deforestation in the region has been changing. It was previously concentrated in rural properties; the majority (44%) of the deforestation occurred from 2019 to 2020 in public forests. The main driver of this change is the land grabbing fostered by land speculation. The land grabbers usurp the public equity of Brazilians – public forests – making fortunes, almost always using violence. They try to take possession of conservation areas and officially implement indigenous lands. However, the so-called “unassigned public forests” suffer the most from the action of the land grabbers. It is an area of 60 million hectares (larger than Spain) of dense forest awaiting the state and federal governments for specification, protection, or sustainable use of natural resources. 30% of the annual deforestation in 2019 and 2020 occurred in these forests.

In addition to land grabbing, the execution of major infrastructure works without performing a proper environmental impact study and illegal lumber harvesting have been driving deforestation. In the last 30 years, an area equivalent to the size of France (78 million hectares) has already been deforested.

Fires (Slash-and-burn agriculture)

Fire has traditionally been used in agriculture and livestock in the Amazon for soil management. The legislation prohibits using fire in vegetation but makes an exception for this practice in certain circumstances. As the increase in soil fertility after fires (Slash-and-burn agriculture) is short-lived, around three years, if the agricultural practice is intensified, new areas for agriculture will be successively demanded.

Fires (Slash-and-burn agriculture) following significant deforestation are the most impactful. They are performed to eliminate trees that have been felled and remain drying on the ground to transform land use for large-scale agriculture and livestock or mining. Although fires (Slash-and-burn agriculture) in the Amazon are spatially limited to deforested areas, agricultural management, and near highways, they can become uncontrolled. In these cases, they cause fires that advance into forests.

Such forest fires can be disastrous, particularly in years of extreme droughts. There was a study on How deregulation, drought, and increasing burnings impact Amazonian biodiversity published in Nature Magazine that shows that droughts and the dismantling of Brazil’s environmental policies are the leading causes of recent fires in the Amazon, impacting more than 90% of its animals and plants species.

Recent data show that forests affected by fire in the Amazon have about 25% less aboveground biomass than intact forests, even after 31 years of being disturbed, leading to forest degradation. Directly linked to landscape fragmentation, forest degradation involves progressive forest impoverishment that is a long-term destructive process. Added to weather events, they also increase the frequency and severity of forest fires.

Under the ox’s paw

According to the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM) study, the area deforested from 2007 to 2016 for agricultural purposes corresponded to 7,502 km2, and reached a production value of R$ 450 million. It seems a lot, but it only meant an increase of only 0.02% to the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

According to the “Atlas da Carne” (Meat Atlas), 2021, developed by the Heinrich-Böll Foundation – linked to the German Green Party – pastures for supplying livestock are the main type of rural landscape in the Amazon, constituting about 63% of the deforested land.

The largest cattle herds are in Mato Grosso (32.7 million heads) and Pará (22.3 million) from the states that make up legal Amazon. It’s no coincidence; they are among the states with the highest deforestation rates in the Amazon.

The dynamics of the sector is inefficient in the way it is done because there is too much land for a few cattle, which is often used to justify and add an air of legality to the illegal occupation of public lands. Institutions, such as Embrapa (Brazilian Agricultural Research Company), have done studies on the potential of sustainable livestock, encouraging good production practices.

Infrastructure projects

There are several infrastructure projects underway in the Amazon. Many of these public works attract large population contingents and end up, for example, boosting illegal lumber harvesting. It is estimated that the construction of a single road can impact from 5 to 5,000 km of forest on each side of its roadway. They are known as fishbones, which end up consolidating human occupation surrounding these highways.

As for hydroelectric plants, there are 137 small hydroelectric power plants (SHPPs) and 44 hydroelectric power plants (HEPPs) operating in the Brazilian Amazon, according to the Georeferenced Socio-Environmental Information Network (RAISG) survey. This number should grow as the construction of over 340 SHPPs and another 107 HEPPs have been planned. Such projects can cause decreased biodiversity, forced migrations of indigenous communities, and decomposition of plant material, causing the emission of greenhouse gases.

Illegal mining in the Amazon

The RAISG survey points out that in 2020, 4,472 localities practiced illegal mining in the Amazon territory in all biome countries, and 87% of these mineral exploration locations were active – mainly gold. The most affected regions in Brazil are the Tapajós River basin, home to the Munduruku indigenous peoples; the Yanomami Indigenous Land, where the invasion of prospectors is estimated as about 20,000 prospectors; and also in northern Roraima, Raposa Serra do Sol in Indigenous Land, which suffered the first major invasion by illegal prospectors in 2020 since its border was defined 11 years ago.

Forest degradation and climate emergency

The Amazon influences the global climate through changes in the carbon cycle and water vapor emission to the worldwide atmosphere. But the global climate also strongly influences the Amazon ecosystem, as tropical forests are sensitive to changes in climate, particularly in temperature and the precipitation rate. Even if Brazil completely stops deforestation today, if the global burning of fossil fuels continues and allows an average global temperature increase of 3 to 4 degrees in the coming decades, the forest may not be ultimately able to maintain its biodiversity as it is today.

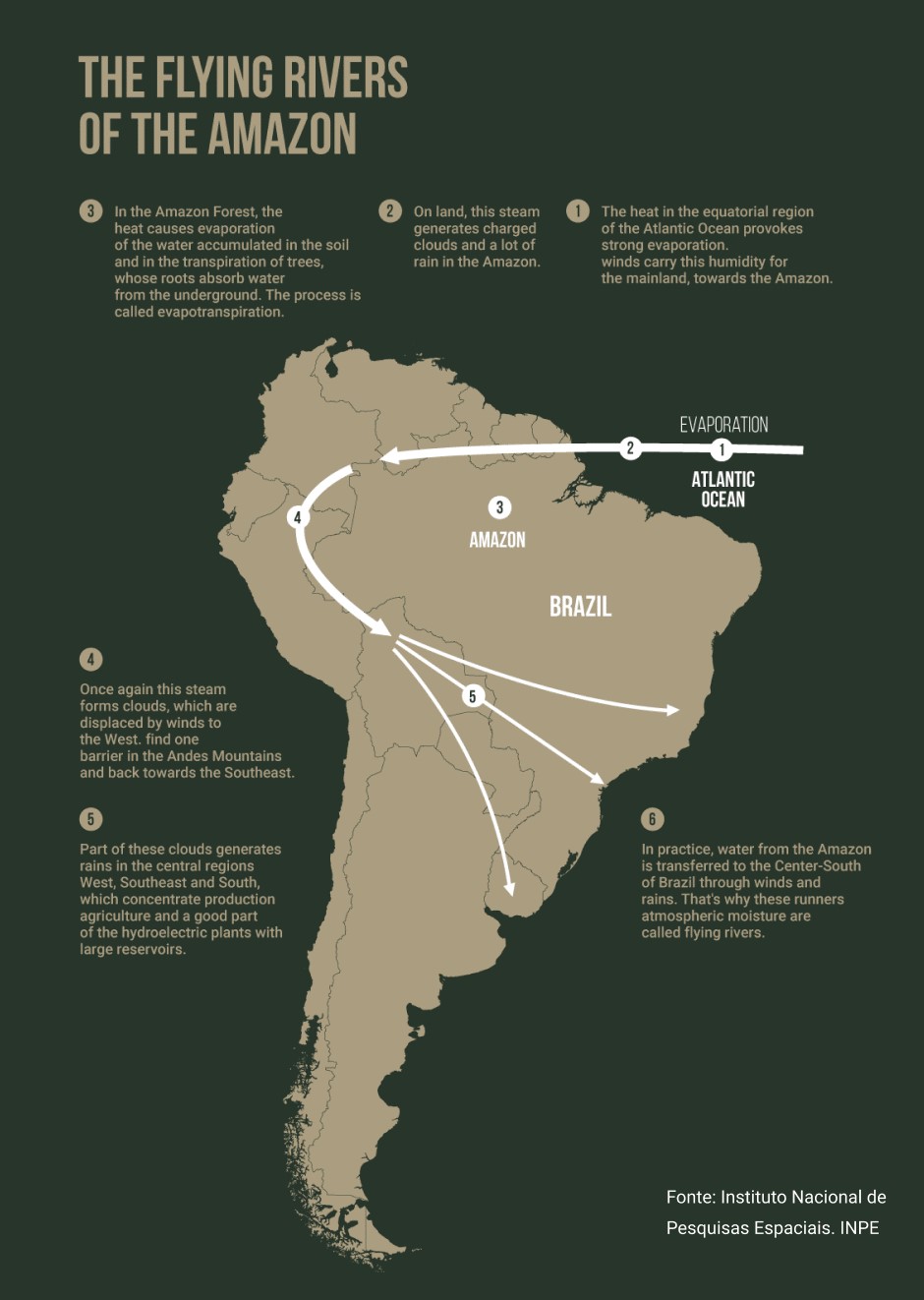

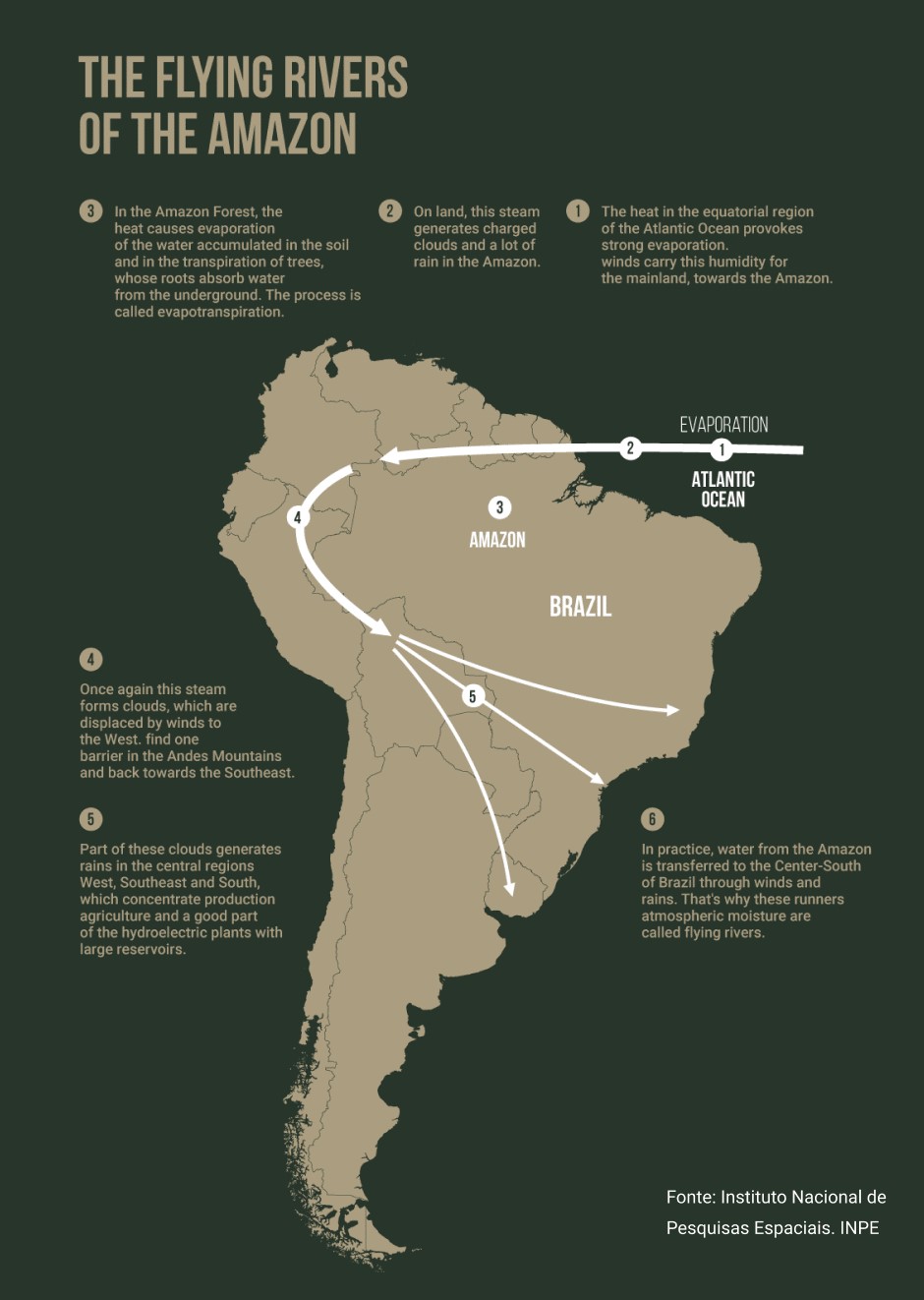

Flying rivers are in check

The Amazon River basin is the largest globally, and its rainforests form an extensive water recycling system. Part of the precipitation in the Amazon comes from the transpiration of the forest itself: it is estimated that every day 20 trillion water is sent to the atmosphere through the evapotranspiration of trees.

This water vapor – which also arrives across the Atlantic Ocean, brought by trade winds – circulates through the region with the help of atmospheric currents until reaching the Andean mountains, where the clouds loaded with water “make the curve” and head towards the southern part of the continent. These are the so-called “flying rivers,” responsible for supplying water reservoirs, watering agricultural fields, and refreshing the cities of the South Central region of Brazil.

But this hydrological cycle has changed due to human action. The reduction of evapotranspiration in the Amazon rainforest is one of the first signs of something wrong in the biome. According to science, as the forest gets drier and warmer, it emits less water vapor and decreased rainfall and carbon absorption from the atmosphere through photosynthesis.

SOLUTIONS ARE AT HAND

We are faced with this scenario of deforestation, global warming, and economic and social losses. The region’s development is backed by sustainability, science, and traditional knowledge to end Amazonian deforestation, which urgently needs to be considered and implemented. It will be necessary if Brazil wants to remain a key country in the production of food, forest products, and the bioeconomy. The following are some actions that can help prevent us from reaching a severe scenario of our forests:

1/ Zero deforestation

We are still able to restore the destruction of the Amazon rainforest. We still have a vast area (80%) with standing forests playing an essential role in water cycling and maintaining the region’s biodiversity. There is an area (10-15 million hectares) in the biome that has already been deforested. It has been abandoned or underused that could be used for the expansion of agroforestry production and we know, as a society, what it takes to reduce deforestation because this had already been done from 2005 to 2012 when the rates of forest falling decreased by 80%.

Stopping illegal deforestation in the Amazon is fundamental for the country’s agricultural production. It is because the forest is responsible for a considerable part of maintaining the rainfall regime. If we consider that and national agricultural production is 95% is unirrigated, keeping forests standing seems to be a wise decision to maintain productivity.

2/ More public policies

To achieve the dream of sustainable development without deforestation, through governance, increased production and protection of rights will become a reality in the region; however, it is essential to implement public policies seeking the valorization of forest assets and promoting the growth of sustainable agriculture and more efficient and concentrated livestock. The development of payment mechanisms for environmental services provided by the forest may be an interesting strategy for communities.

3/ Sociobiodiversity and economics

Commercializing sociobiodiversity products or promoting ecological tourism in the region are also essential components for Amazonian economic development. Strengthening family farming supplies food for many Brazilian tables and is one of the ways to ensure forest conservation. Providing quality technical assistance can help them improve their alignment to production practices for promoting local opportunities, increasing family income, improving livelihoods.

4/ Increased efficiency of agriculture

Modern, productive, and sustainable agriculture is also a vehicle for forest conservation and regional development. It is necessary to encourage increased production through investments aimed at sustainable “productivity” to do so. Financial and credit incentives for agriculture should aim to improve productivity and social and environmental sustainability, freeing production from dependence on new deforestation.

5/ Sustainable livestock

Extensive cattle farming (<1 head/hectare) has to end if we want to continue producing more meat without destroying the forest. For example, if productivity were increased from 60 kg/ha/year to 150 kg/ha/year in only 21% of the existing pasture area in the Amazon (11.5 million ha), it would only take another 4 million ha to meet the federal government's meat production target – to produce 34 million tons of meat from 2030 to 2031. Modern ranchers are increasingly engaged in more productive and environmentally sustainable livestock procedures.

6/ Major defined borders of Indigenous Lands and creation of Conservation Units

Indigenous Lands (ISTs) protect the forest from deforestation and degradation, maintain the global climate balance, and maintain food production. The blockade of deforestation in the Amazon promoted by ILs (Indigenous Lands) also represents a fundamental element for Brazil to abide by the commitments made in the Paris Agreement. Another essential point is the creation of Conservation Units (CUs), which are forest areas protected by law because they display special and often unique ecosystem characteristics.