You are in:

Millennial Amazon

How to browse

Click on the icons to move around the room or to access points of interest. Alternatively, use the arrow keys to turn, go forward, and go backward.

Click and drag the image to explore the scene in 360°.

Alternatively, use the arrow keys to turn left and right.

Use the scroll wheel to zoom in or out.

Alternatively, use the plus and minus keys.

Virtual Tour / Texts, maps and data on the topic

Texts, maps and data on the topic

INTRODUCTION

When one thinks of the Amazon, a distant reality comes to mind. For some of us, it is only a forest, isolation, animals, and where some indigenous people live… Contrary to common sense, the Amazon is the largest tropical forest globally, and there are unique ecosystems and great social diversity there. In addition to important urban centers, most of the indigenous population in Brazil live there.

The Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), responsible for conducting the Demographic Census in Brazil, calculated that 84% of the 896,000 people who declared themselves or considered themselves indigenous in their last official survey (2010) lived in the Amazon region.

However, the Amazon, a common home of different ethnicities, cosmologies and traditions, is threatened. The advance of urbanization, the climate emergency, and the lack of functioning of public policies are some factors. Why do we, as a society, ignore the impacts of these threats on indigenous peoples?

LIVING IN THE RAINFOREST, LIVING FOR THE RAINFOREST

The experience of indigenous peoples is intrinsically linked to the territory where they live and what was passed on by their ancestors. The graphic elements found in body paintings, ceramics, braids and artifacts, as well as in today’s featherwork, enables this linkage to this common past.

Indigenous peoples teach us that nature and culture cannot be separated, and therefore do not oppose each other. We still have a great deal to discover about the necessary dimension on how living beings and all their species coexist – that must be the resilience of rainforests.

Deforesting the Amazon means liquidating its resilience. The original peoples retain ancient knowledge. Medical sciences are dedicated to exploiting the biological assets of nature, capable of reproducing them synthetically. But only a minute part has been observed.

Food production

Indigenous societies dominate the cultivation of many plant species, including selecting specimens and seeds featuring advantageous attributes, whether productive or adaptive, which has led to the domestication and production of numerous varieties over the past thousands of years. Indigenous croplands produce plenty of food and, in several indigenous societies, hunting and fishing complement the family diet.

One example is domesticating cassava, a plant that has spread among many indigenous peoples. It was necessary to select varieties with extremely low levels of toxicity to consume these roots until finding a product with only trace levels, which could be used as food.

Sieves, mats, “tipitis” (cassava strainers), fans, pots and oars for mixing the cassava meal while roasting it, as well as other utensils. These are part of the cultural tools related to cassava processing.

Spatial mobility

Most indigenous societies in the Amazon practice constant spatial mobility. It is not just a subject of living as nomads but the strategic management of natural resources and social reproduction. As they understand the regenerative capability of forests, cultivating the most useful species for building houses, producing artifacts, feeding game animals, and so on.

The villages are usually consolidated around recently opened croplands and not otherwise. Therefore, a family who has more than one cropland and is using the older ones as the new croplands do not produce all the plants necessary for supplying the food safety of the group.

This systemic occupation is what keeps the forest standing, healthy, and diverse. Moreover, it demonstrates there are no virgin forests, on the contrary; they result from a long and constant process of gardening and conscious building of a viable landscape for coexistence among living beings, which only exist because of this integration.

Connecting to the world

Colonization arrived in Brazil and didn’t ask permission, according to what the ancient peoples stated. Europe colonized Africa, Asia, and the Americas, and instituted a seductive system: distributing goods to the natives in exchange for their lands. And that is how it took place; there were efficient machetes, axes, and metal pots, as well as contaminated clothes, forced evangelization, and the oppression of slave labor.

Even so, the indigenous did not succumb. Generations after generations have created resistance to diseases, learned Portuguese to understand the laws of the colonizer, and to this day are using objects and technologies that are favorable to them to continue existing in the world around them and avoiding new forms of oppression.

Many indigenous communities nowadays have satellite dishes, solar panels, internet, mobile phones, aluminum boats with outboard motors, power generators, as well as more practical utensils for everyday life. Indigenous peoples are active on social networks and their exchange with the world is active due to the Internet. Traditions are maintained even though modernity has arrived.

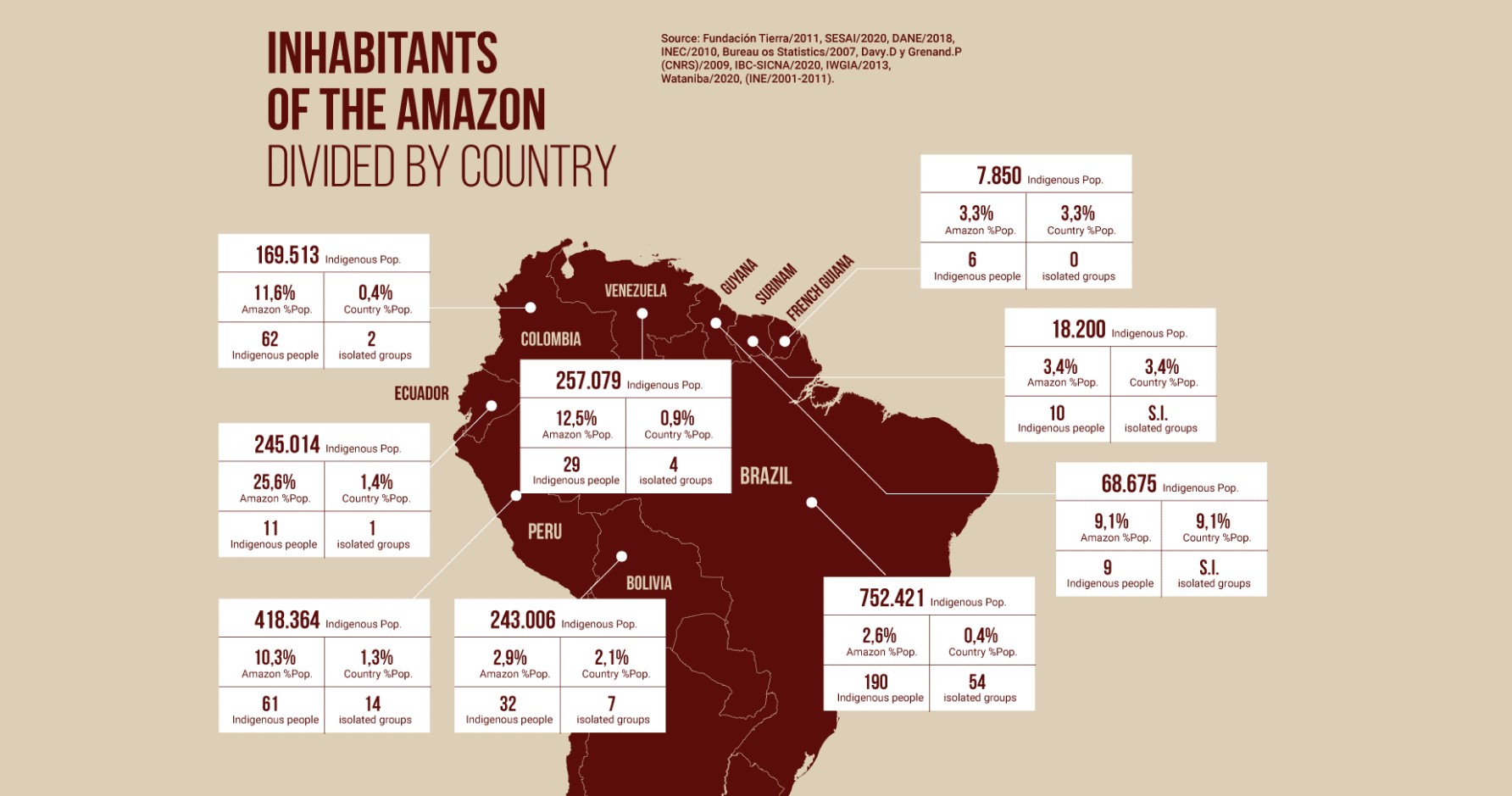

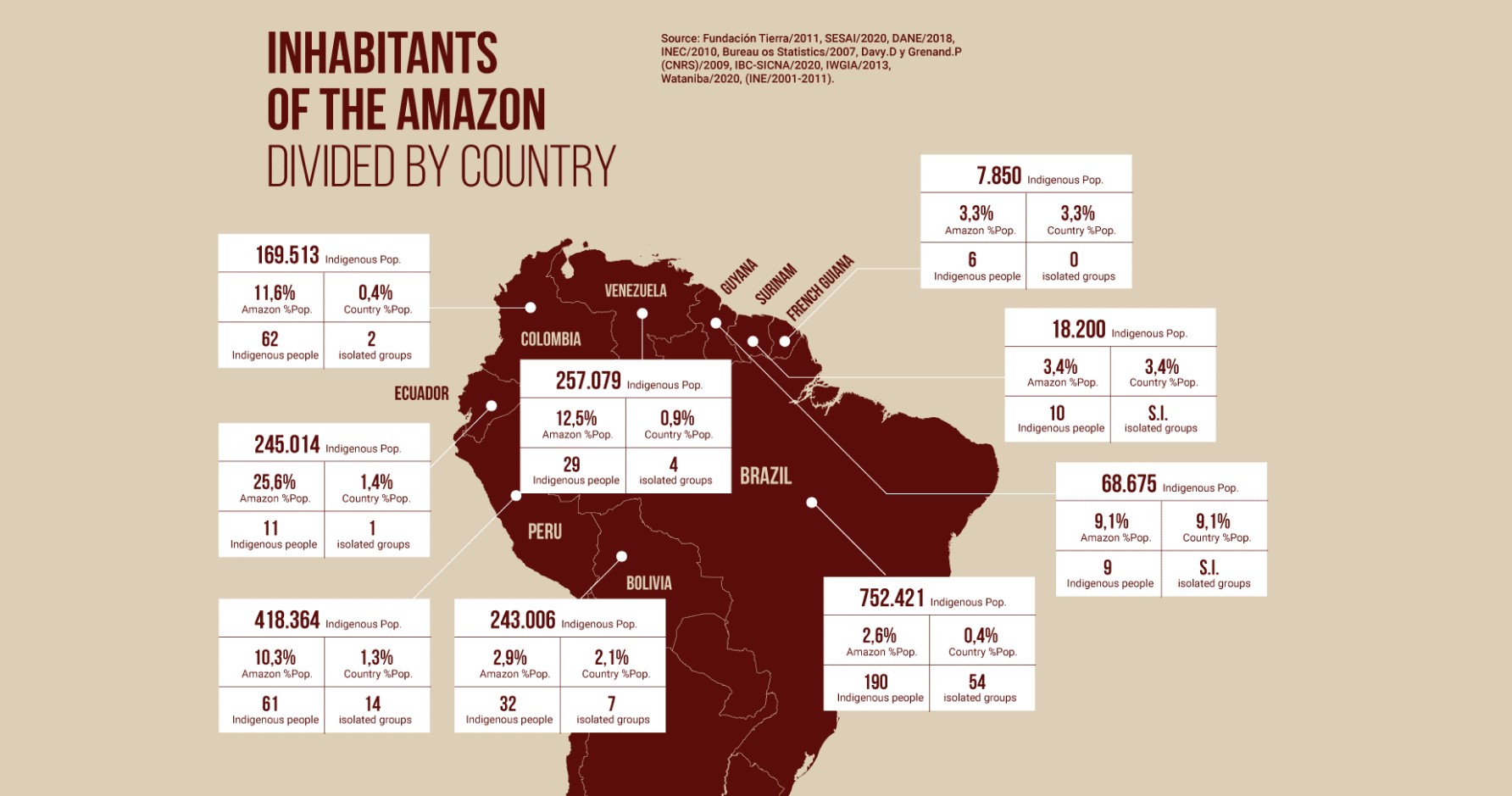

INDIGENOUS POPULATIONS AND AMAZONIAN LANDS

Data from 2020 conducted by the Special Secretariat of Indigenous Health, SESAI, indicate that 752,421 indigenous peoples from more than 190 indigenous peoples live in the Legal Amazon – an area that encompasses nine Brazilian states. That total corresponds to 2.6% of the population living in the Amazonian territory, estimated at 29 million people according to IBGE/2019.

Indigenous peoples have gained fundamental rights regarding Brazilian sociodiversity. Their social organization and their languages are recognized and must be exercised; the borders of their territories must be defined and protected by the State; they can speak for themselves, through their organizations and without the intermediation of guardianship instruments; they can implement their education and health systems with state resources, among other rights.

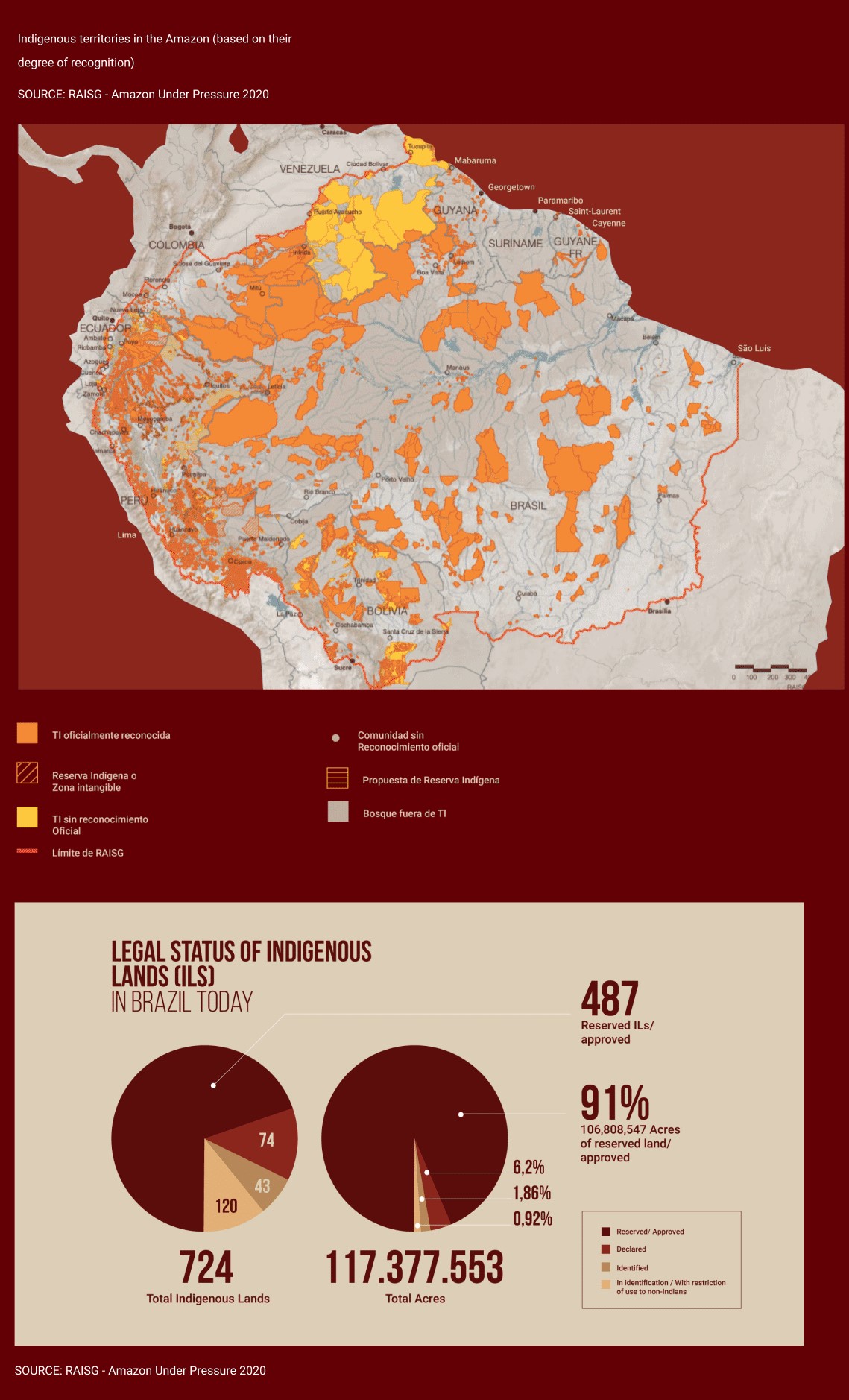

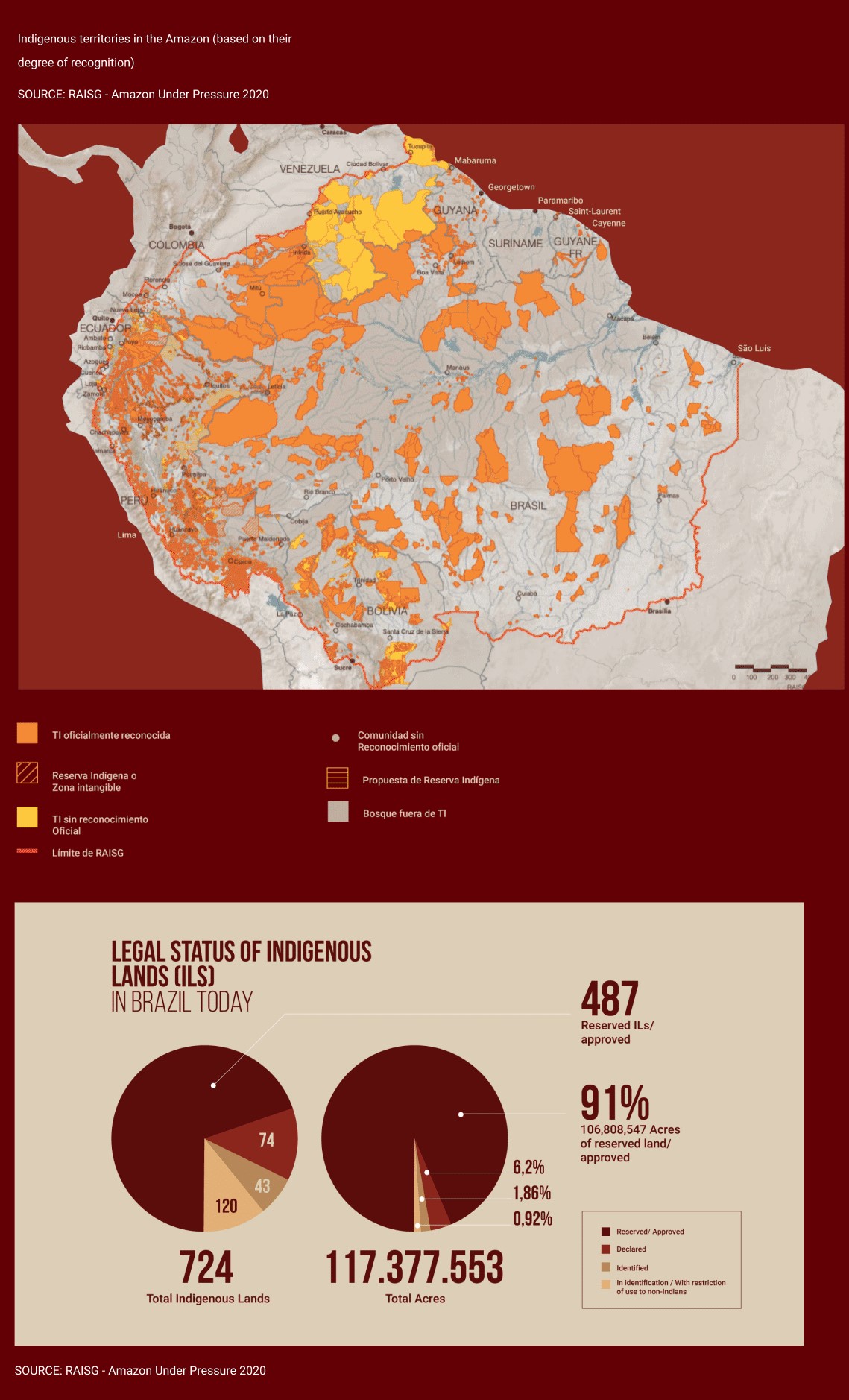

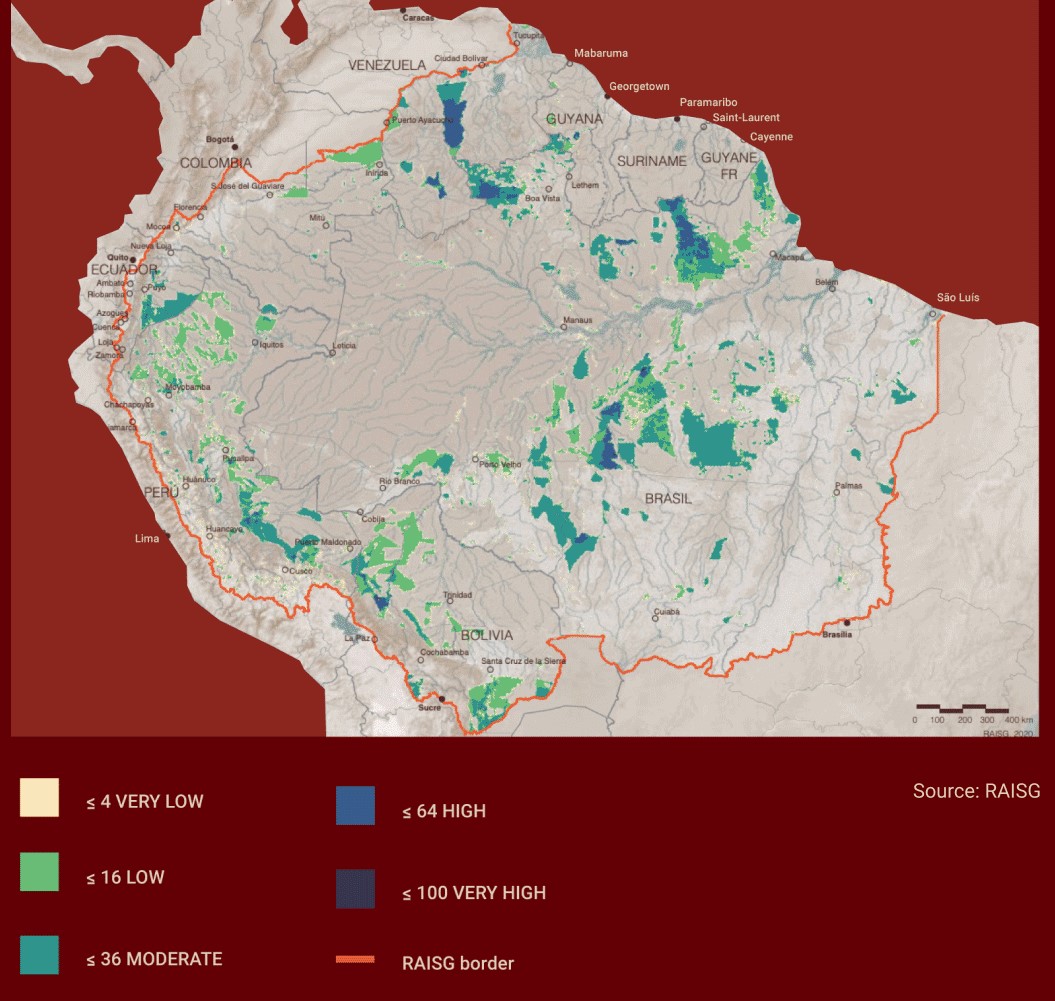

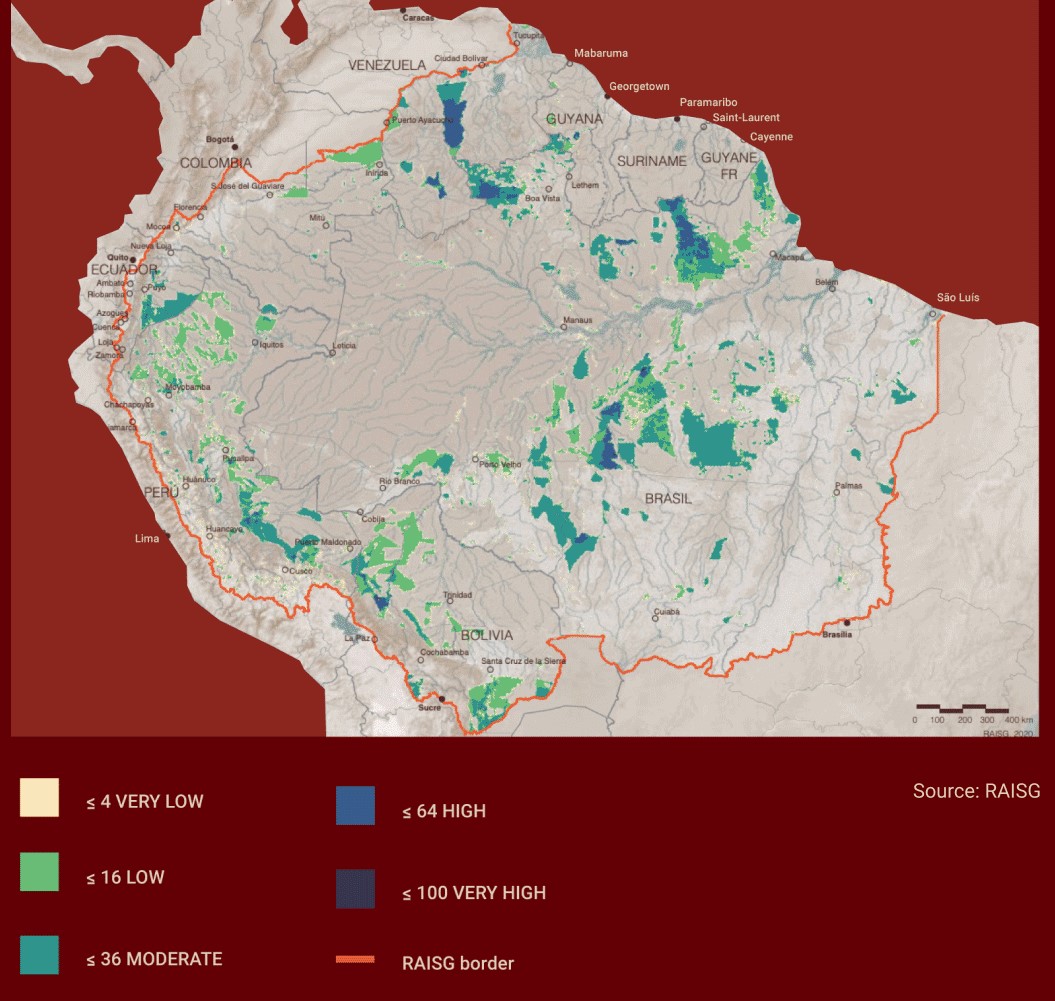

Indigenous Lands (ILs) are a reflection of traditional peoples’ way of life, their rightly owned lands. They end up acting as a barrier to deforestation and degradation, in addition to storing carbon. Even so, they are under pressure from mineral and timber resource exploitation, usually preceded by illegal invasions.

Data from the Amazon Georeferenced Socio-Environmental Information Network (RAISG) show that 42.2% of the Amazonian territory is protected as natural areas and indigenous territories. There are 424 ILs in the Brazilian Amazon. According to the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM), these Indigenous Lands could function as a “green ocean”, supplying the region with enough moisture to maintain its rainy and mild climate, as long as they are not subjected to continuous deforestation, as has been observed.

Indigenous Lands need to be identified, borders need to be delimited, physically demarcated, approved and, finally, registered with the Secretariat for Coordination and Governance of Union Heritage (SPU). The whole process is assigned to the National Indian Foundation (Funai), and it has taken many years of studies, analyses, and revisions.

The demarcations made in recent years are in danger because of the “Time Frame”, a thesis that advocates that only those occupied by them can be admitted as Indigenous Lands until the 1988 Constitution.

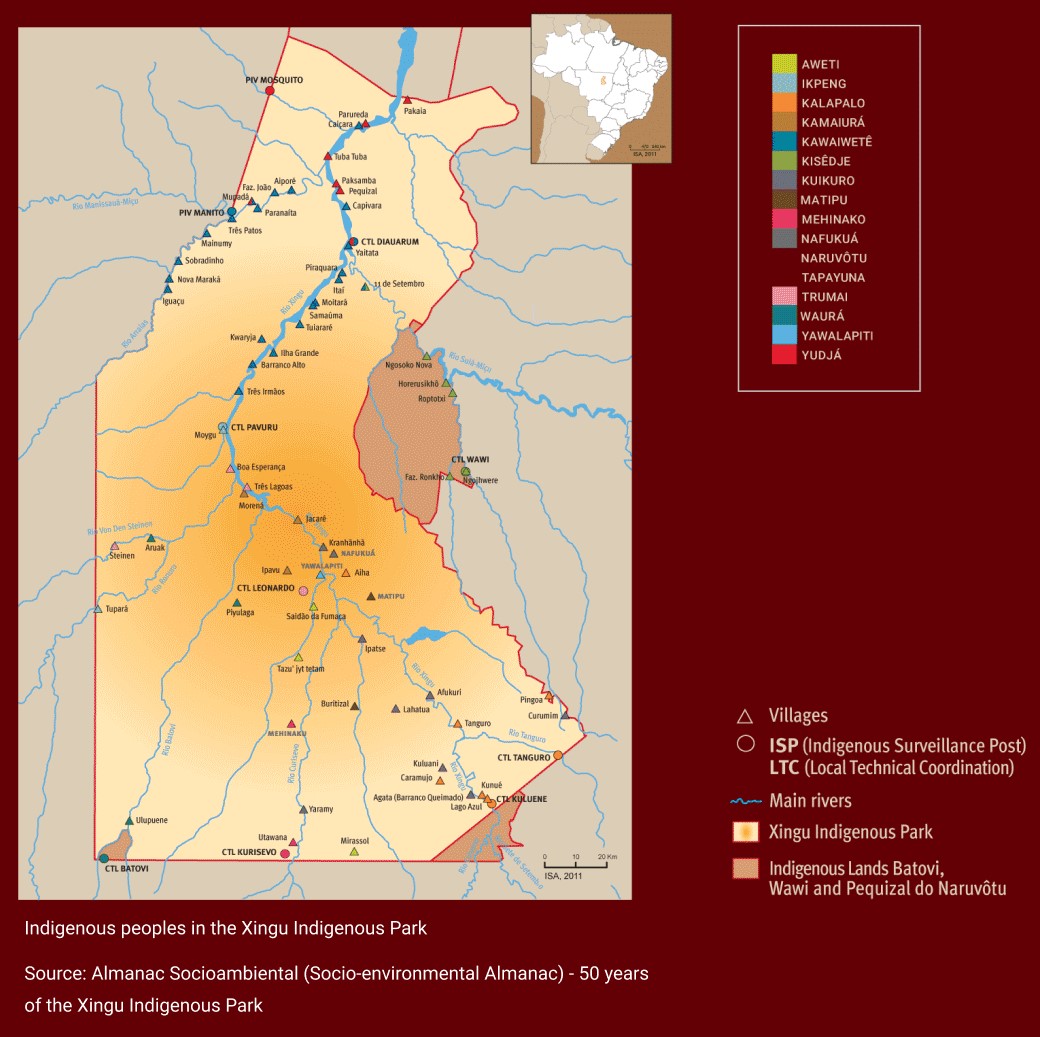

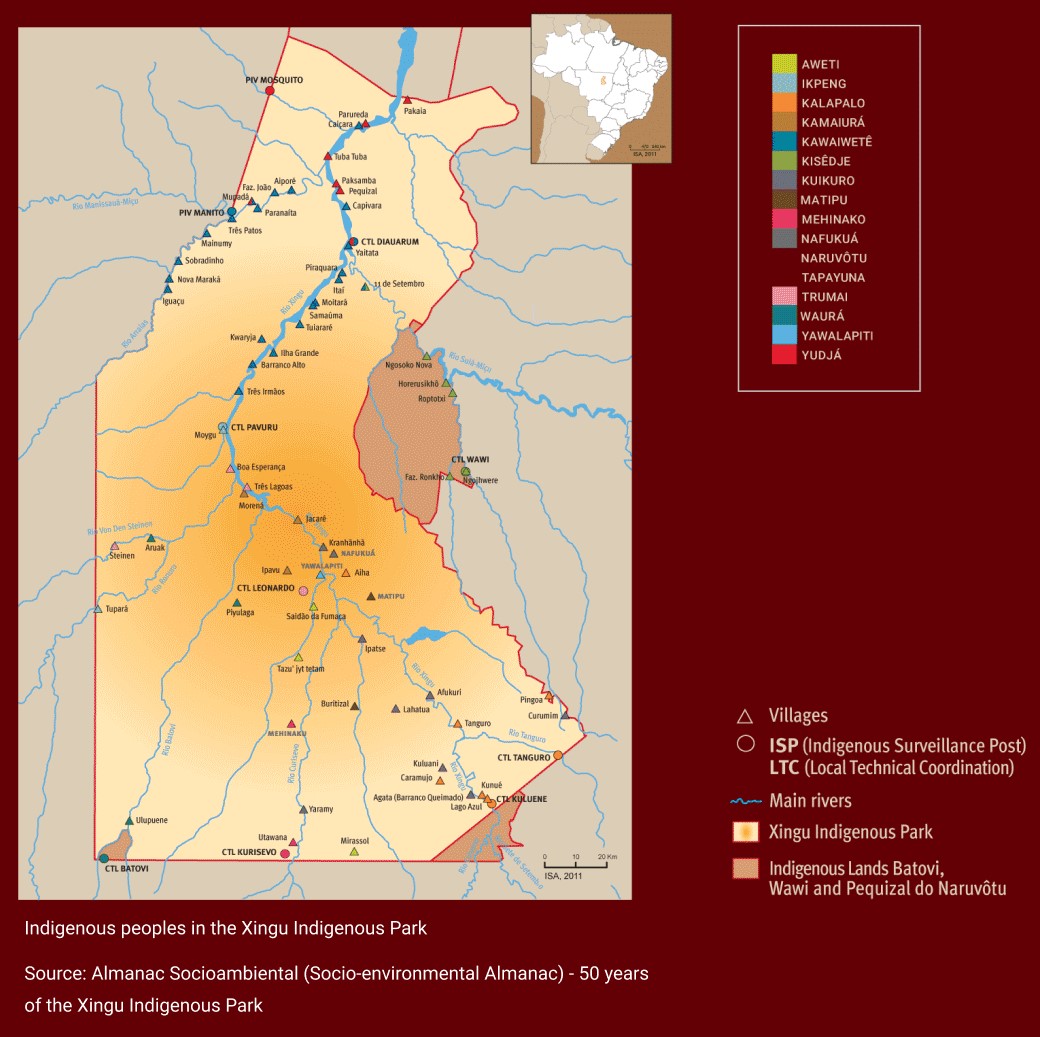

Xingu: conservation is endangered

The Xingu Indigenous Park (PIX), turned 60 in April 2021 and there are 16 indigenous peoples in its territory with the Aruak, Karib, Tupi-Guarani and Jê language families. This is an example of the importance of ILs as barriers to deforestation. Research indicates that the substitution of native forests by cultivation of pastures or agricultural crops in the region may lead to an increase in the regional temperature of 6.4°C for the forest-tillage and 4.26°C for forest-pasture transitions. Significant increases such as these have a direct consequence in the decreased volume of rain – causing certain damage to the agricultural production of the region and to the absorption of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

According to the Socio-environmental Institute (ISA), from 2018 to 2020, 513,500 hectares were deforested in the Xingu River basin, equivalent to four times the city of Rio de Janeiro (RJ). One of the epicenters was in the forest strip that maintains the biome moisture. These data reinforce how strategic the protection of indigenous territories occupied and managed by their residents. We must do this to control the climate crisis and maintain the well-being of the population on our planet.

Isolated or recently contacted peoples

Many isolated indigenous peoples live in areas that are not always protected. Even those who are cornered, avoid contacting Brazilian society. The National Indian Foundation (Funai) is responsible for monitoring and protecting these peoples. According to 2017 data from Funai, there are records of 114 isolated or recently contacted indigenous peoples in the Amazon.

PRE-COLUMBIAN AMAZON

Human beings have occupied the Amazon for at least 11,600 years. Discovering and uncovering how human societies from the most remote past occupied what today corresponds to the Amazon will help us act now to preserve their future. In other words, social, cultural and historical processes are responsible for the domestication of the landscape for the benefit of the living well perpetuating life.

More recent interdisciplinary studies, coordinated by Brazilian and foreign archaeologists, show that before the arrival of Europeans; there were human settlements, and the Americas who organized economic and political entities, which maintained extensive communication networks, built bridges, dams and canals, performed ground leveling, cultivated croplands, and intentionally replaced “useless” forests for “useful” forests, such as Brazil nuts or açai palms.

There are indicators supporting the thesis that the Amazon is only what it is today because its original peoples had extensive and in-depth knowledge of how to interact in their environment. Archaeological research indicates how indigenous peoples occupied the region, making it ‘productive and pleasant’. One of these legacies is the Indian Black Land.

INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES

The constant attacks on the Indigenous Lands also threaten the survival of the languages originating from these peoples, harming their oral traditions, their artistic forms (poetry, music, oratory), their knowledge and cosmological perspective. Linguistic diversity and cultural diversity occur side-by-side and, based on this concept, linguistic loss implies a catastrophe, both locally and for humanity as a whole.

Languages spoken in the Brazilian Amazon

According to the Atlas of the World’s Languages in danger of extinction, almost half of the 6,000 languages spoken today in the world are heading for extinction in the very near future. By 2100, it is expected to only have 670 languages left. Currently, in continental Amazon, there are around 410 indigenous peoples (190 of them in the Brazilian Amazon). It is estimated that more than 200 indigenous languages are spoken throughout Brazil.

Virtually all linguistic branches and linguistic families classifying indigenous languages in Brazil are present in the Amazon.

In the border regions or cultural areas, such as the Xingu Indigenous Park (MT), the “Alto Rio Negro” (Upper Black River) (AM) and the “Tumucumaque-Trombetas-Mapuera” Complex (AP and PA), it is very common to see indigenous speakers three to five languages, sometimes more. In the “Alto Rio Negro” (Upper Black River), for example, there are polyglots who speak from eight to ten languages fluently, including Portuguese, Spanish, and “Nheengatu.” The latter is called the General Amazonian language, it was based on “Tupinambá” and it is spoken throughout the Brazilian Amazon valley to the border of Peru, Colombia, and Venezuela.

CHALLENGES FOR PEOPLE OF THE FOREST

The original people from the Amazon have suffered constant threats and hindering their way of life. The absence of supervision by government institutions and pressure from political lobbies for the approval of legislation that makes changes in territorial recognition processes have benefited predatory activities, such as mining and logging.

Environmental degradation in Indigenous Lands

38% are in Protected Natural Areas and Indigenous Lands have been impacted by environmental Amazonian degradation. Logging, illegal mining, and the cultivation of illegal plants for consumption are the three economic activities employing thousands of people and proliferating in the rainforest, supported by the demand for their products in international markets.

Climate emergencies

We are experiencing a climate emergency due to the rising temperature of the planet caused by the release of polluting gases into the atmosphere. This fact has been proven by scientists pointing to a greater number of extreme climatic phenomena, threatening the food, water, and economic security of many regions, including Brazil.

The indigenous movement demands public policies to adapt and prevent the effects of climate emergencies, such as droughts, fires, and changes in the rain cycle, contemplating indigenous populations, whether they are on their own land or not.

Covid-19 pandemic

At the end of February 2020, Brazil confirmed the first confirmation of Covid-19. That year in April, the first case of an infected indigenous person was recorded; it resulted from contact with a doctor who was symptomatic of the disease.

By the beginning of August 2021, when Covid-19 had caused more than 550,000 Brazilians deaths, the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (Apib) recorded 1,162 deaths and 58,000 reports of contamination among indigenous peoples from 163 ethnic groups.

According to the organization, there are several challenges related to indigenous health and coronavirus prevention. These are as follows:

– The vulnerability of indigenous peoples to diseases, due to poor social, economic, and health conditions than those of non-indigenous peoples, amplifies the potential for spreading diseases;

– The lacking infrastructure of the Subsystem of the Unified Health System (SUS) was created to meet indigenous health needs;

– The way many people live provokes exposure to infectious diseases, as people living in cities are not subjected. Most indigenous peoples live in collective housing, and it is common for many of them to share utensils, such as gourd vessels, bowls, and other objects, favoring contagious situations.

CLEAR SKIES FOR FLOATING

The new technologies have been used by various indigenous ethnic groups as a resource for them to tell their stories themselves. Adapting to the new, but without putting aside tradition, mobile and the Internet have integrated into the day to day. In Waujá, the language of the Aruaque family, the Internet has become enunakuwa — clear skies for floating—and yuntagapi cell phone—used for sharing information.

HOW TO CONTRIBUTE

How can you help and add value to the lifestyle of indigenous peoples? You can engage in the following three projects:

- The Organize Protection campaign is an indigenous proposal for containing the devastation of Brazilian biomes. It was launched during The 2021 Indigenous April event, the initiative seeks to raise awareness on the importance of the work performed by indigenous organizations defending their territories and associated biomes.

- It is based on the concept of Socio-environmental Diversity Territories, the “Origens Brazil©” (Brazilian Origins) seal has enabled synergy among peoples from the Amazon Forest whose lands are linked to protected area corridors. The traditional ways of life and indigenous populations result in environmental services and generate marketable products, without any negative impacts to the physical integrity of the forest. It is centralized in regional canteens, the products are transferred to marketing and consumer chains.

- “GaleriAmazônica” (the Amazonian Gallery), in downtown Manaus. It is a socio-environmental business defending the rights of rainforest peoples by valorization of their traditional ways of life and knowledge. It has served craftspeople from over 40 tribes, represented by its associations and cooperatives, and it operates on ethical trade principles.

- An Isolated or Decimated Petition of the Coordination of Indigenous Organizations of the Brazilian Amazon (Coiab) and the Observatory of Human Rights of Isolated Indigenous Peoples and Recent Contacted so that isolated indigenous peoples continue that way. It is possible to sign the petition to exert pressure on the government to renew the ordinances that protect these peoples and their territories: www.isoladosoudizimados.org.